“When we hear that the Gross National Product has grown, instead of cheering, we should ask exactly what has grown, for whom, at what cost, and at whose expense. Even better, we should work to develop indicators of national progress that reflect more accurately our real value and our real welfare.” —Donella Meadows, 1988

In 2012 Vermont became the first state to officially adopt the Genuine Progress Indictor (GPI) in state legislation. It was a big step and an important one—a step that would help move Vermont closer to measuring its progress by more than growth alone, as with the Gross State Product. Instead, it would factor in the health of our ecosystems, the equality of our communities, and the wellbeing of our families.

Recently, the Meadows Institute was excited to take another step in that direction by convening a day of discussion that included representatives from the state government, nonprofit organizations, statewide networks, the educational community, and more. We were joined by a group from UVM’s Gund Institute for Ecological Economics, which has spearheaded research and development of the GPI, as well as the New Economy Coalition (NEC), a nationwide group at the forefront of the movement for more sustainable, inclusive, and resilient economies.

At the Meadows Institute, we see transforming the economic system as a major leverage point on the way to a desirable and sustainable society. At the GPI talks, we were interested in how to use the GPI for economic transformation, both in Vermont and beyond. “It really becomes interesting when measurements can become drivers of behavior…Vermont’s GPI could be a game changer with ripple effects around the world,” said NEC President Bob Massie. With twenty states currently considering GPI legislation, including Oregon, Maryland, Hawaii, and Utah, Vermont just might have that chance.

So what is the Genuine Progress Indicator, anyway?

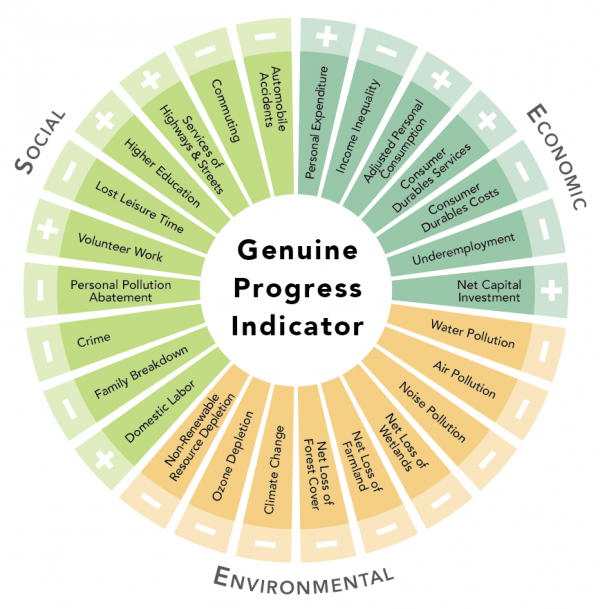

This graphic shows each of the 26 indicators and how they affect the overall GPI (image developed by the Donella Meadows Institute, 2014)

At its heart, the GPI is a measure of economic wellbeing alternative to the traditional Gross Domestic Product. Whereas the GDP measures how many things were produced and how many things were bought and sold in the market in a given year, GPI measures the impact of that economic activity on our lives, our environment, and on our social wellbeing. Higher levels of volunteer work and educational achievement make the GPI go up, societal harms such as water pollution, greenhouse gas emissions, or family breakdown make the GPI go down. Big disparities in income distribution also lower GPI.

Consider crime as one simple example: a house is broken into and needs repairs to its door and security system. GDP goes up because of the money spent on the repairs. GPI instead goes down as it counts expenditures on security devices and repairs as a measure of how unsafe and less livable the community is.

Similarly, if a tract of forestland is turned into a soybean monoculture, GDP will account only for the goods and services that development brings. GPI will account for these things, but also for the associated negatives—loss of habitat and ecosystem services, increased pollution, decreased recreational opportunities, and more.

It’s easy to see why this more holistic approach could be a reality check on our progress. But how can we turn the GPI into a tangible set of goals for a genuine progress agenda, one that is widely shared by policymakers and citizens alike?

Leaders at our discussion agreed that the biggest hurdle right now is communication. Andrea Colnes, Executive Director of Vermont’s Energy Action Network, explained the challenge: “It’s not teaching people how to work with GPI; it’s teaching people to value what matters, freeing them up, making them aware of the big picture.” As Ken Jones, Economic Research Analyst at the Vermont Agency of Commerce & Community Development, said, “Whenever there are these opportunities about a policy decision that has economic impacts, we need to note how GPI is affected and how it differs from traditional measures.”

The good news is that Vermont already has many great examples of effective communication and networking toward a shared goal, and many stakeholders are already working on aspects of the GPI from renewable energy to income inequality. As an institute and a community of leaders committed to real progress, our next steps will be to build a constituency around the GPI, generate accessible examples of how it can be applied, and begin sharing the story of GPI as widely as we can.

The other good news is that this effort is one you can be a real part of! If, like Donella Meadows, you believe that indicators of progress should be about “real value and real welfare,” then start to share the story of GPI with your family, friends, and community. The more people who are behind a measure of Genuine Progress, the faster we’ll get there.