The following essay on the powers that shaped a life–including Donella Meadows’s Limits to Growth–was written by Erik Esselstyn for his Yale 50th Reunion, October 2008.

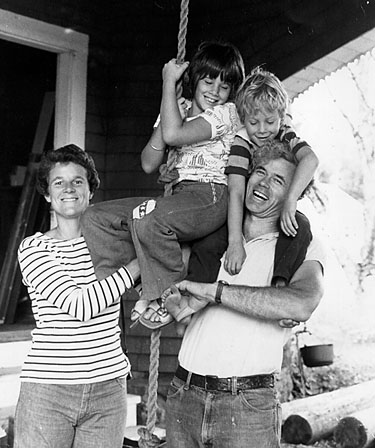

The Esselstyn family photographed in Blue Hill, Maine, 1978.

A thousand guiding values thread through our lives. In searching for a theme, some linking thread, that flows through my entire life and ties together my many careers, I would identify a braid with four strands: land, loss, limits, and a love of words. My earliest memories are rooted in the seasons and soil of a Hudson Valley family farm. And today, edging into my eighth decade, my heart still lifts cresting that last hill on the drive to the farm and seeing the ancient Catskills and forty miles of the Hudson River spread before me. Devotion to a land conservation ethic has long been part of my DNA.

Loss sculpts all our lives. Each of us has known death as our parents and longtime friends have died. At this stage in our lives those losses and memorial gatherings kindle gnawing questions about how our own deaths might unfold. And we wonder with a whiff of hopeful uncertainty, “what might people say at our memorial service?” I would make the case that profound loss in our youth spawns a different set of questions. My younger brother died when I was six, my mother when I was eight. I believe the response patterns chiseled into my value system by those early losses came into focus as “How can I help?’ and “How can I make it better?” I have always rooted for the underdog, the little guy, and for voiceless nature.

My awareness of limits took root in a farm boyhood and blossomed in my mid thirties on encountering one slender paperback. Donella Meadows’ 1972 book, “Limits To Growth,” made sense scientifically – and it fit emotionally. I sent copies of that book to every member of my family and a number of close friends. From Donella Meadows’ writing I understood for the first time the inescapable implications of exponential growth. Decisions about having two children, decisions about long term timber investments, and decisions about time invested in putting land into public trust all derive their edge from that insight about limits.

My love of words began in childhood. The death of my younger brother in a farm accident meant the loss of my closest playmate. Looking back, I know part of my grieving soul found healing in a devotion to books. My parents enrolled me in two monthly children’s book clubs. Each new arrival, immediately devoured, soon boasted my personal bookplate. And at evening dinner whenever a question about a word’s meaning arose, it was Erik who went to the looming Webster’s Unabridged in the library. I would flick on the tiny brass lamp, memorize the derivation and meaning, and, then, beaming, give a careful report at the dinner table.

Like some powerful yet unseen compass, this quartet of values has guided all my career decisions, shapes today’s heartfelt conversations, and fuels my profound concern about humanity’s future on the planet. Leaving Yale as an English major, I spent my military service with the 82nd Airborne. My role: a writer with a TOP SECRET clearance. And during my courting years in Boston I worked as a writer in a town planning firm. The wordsmithing continued when I taught high school English for two years when my wife, Micki, and I took turns supporting each other through graduate school. No question that the love of words exerted a monumental influence on my early job choices.

Midway through my final year at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education I decided to focus my newly honed administrative skills in community colleges. Imagine such offerings as Piano Tuning, Bee Keeping, Construction Equipment Repair, Nursing and, of course, the History, English, Math, and language classes to move on to a four year college. Without a doubt my commitment to the little guy, the underdog, played a part in pulling me to a huge community college in Charlotte, NC. I was Dean of Students, shepherding an enrollment of more than twenty thousand.

Charlotte’s exploding population and relentless construction offered anyone with an environmental itch their pick of battles with developers. My choice: efforts with a dogged coalition to save six in town acres and a Civil War era brick chapel from becoming a parking lot.

Those efforts more than thirty years ago mean that today I can show my offspring St. Mary’s Chapel Park with towering water oaks, rolling lawns, and a tiny refurbished chapel, the site of weddings, art exhibits, and string ensembles – booked months in advance.

Also in Charlotte I began one of my life’s most profound personal seminars, triggered by a lethal cancer and a one per cent prognosis. Why does your own body turn against you? The decision to learn guided visualization and to teach the healing technique to other cancer patients lead to a new career, a new life on the Maine coast, and Micki’s and my teaching other couples how to traverse the rocky path of life threatening illness.

The seaside village of Blue Hill in the late 1970’s called out for ways to protect its matchless views and open land. A three year effort of education and the meticulous recruiting of a board heavy with local Mainers produced, in 1984, the Blue Hill Heritage Trust. One of the highest of my lifetime highs. Today the trust conserves more than 5000 acres of farm land, woods, and coastal vistas.

An eventual move from Maine and a decade living just off Whitney Avenue in New Haven meant Benny Goodman in Woolsey Hall and the Yale Precision Marching Band on fall Saturdays. Our family delighted in demanding schools, ethnic restaurants, and food markets an easy walk from the house. And when my visualization practice faded, I began a two year program at Yale’s School of Forestry and Environmental Studies – a sleuthing into the mysteries of soil, air, water, and forests. Yes. Oh, yes, there are environmental limits. And our unbridled growth devours the very natural systems that sustain us. Stalwarts in Yale’s Economics Department even today belittle Donella Meadows’ thesis about limits. And our species nods numbly to their Jiminy Cricket mantra that a finite planet can support infinite growth.

One of my lasting memories of the Forestry School is the incredible talent and commitment of students half my age who will spend their careers confronting the environmental disaster our generation has left in their path.. An internship with the United Nations in Brazil extinguished any wisps of doubt about the need for limits. Armed with a Masters in Environmental Management and Micki’s support, I moved our home to Gainesville, FL. What more idealistic role than factotum in a tiny start up there making photo voltaic panels?

A vertical learning curve, enlisting the Muse to help woo angel investors, and generous loans from family did not prevail. Solardyne Corporation’s dreams of electricity from sunlight evaporated after three hectic years. I spent the remainder of our Florida incarnation heading up an environmental non-profit. We worked with local developers to shift to Energy Star building standards. The resulting major reductions in electrical use benefitted the buyer, the builder, and the banker. And Gainesville’s coal-fired energy plant puffed out a little less pollution.

In 1999 Micki died after a ten month odyssey with brain cancer. I proffered every visualization nuance I knew. And I wrote fiercely eloquent inquiries to medical centers from California to Italy. Growing despite intense radiation, the entrenched glioblastoma maintained the upper hand. Thirty-three amazing years together. So many assumptions about our future. You know the one about clanking wheelchairs together in our nineties on the porch of some assisted living facility. All gone. I cherish the memories plus her singing and her features living on in our children. (See esselstyn.com.)

The fiftieth reunion, for me, marks the start of the final quarter. I have remarried, a widow, who, like Micki, fills the house with song. We live on a Vermont farm that produces potatoes and squash to store in the root cellar and enough fresh garden stuff to delight this vegetarian. The conservation ethic, the concept of limits must be widely understood. Procrastination’s no longer a tenable excuse.

My deepest hope is that I can finally call up my full voice to write about land use, human numbers, and limits – offering options to make things better for the generations that follow. Death and I have danced together many times. I know of no better use of the message from those encounters, that life is indeed finite, than to marshal my final energies on behalf of the planet.

Erik Esselstyn currently serves on the Donella Meadows Institute Board of Directors and was one of the founding members of Donella Meadows’ Cobb Hill Cohousing community.