Luigi Piccioni1

Dipartimento di Economia e Statistica,

Università della Calabria, Ponte Bucci 0C, 87036 Arcavacata di Rende, Italy

www.ecostat.unical.it/Piccioni

email: l.piccioni [at] unical.it

Read the PDF version of this article

Contents

- 1. The planetary success of an unusual work

- 2. On the origins of The Limits

- 3. Positive opinions and relaunching efforts

- 4. Economic discipline, between disorientation and rejection

- 5. The Catholic Church, from the initial interest to the clash on the demographic policies

- 6. A fine capitalistic plot: the interpretation of the left

- 7. The oscillation of the young Italian environmentalism

- 8. The indifference of the institutions after the short attention of Fanfani

- 9. The Limits forty years later: a mixed balance

- Bibliography

Exactly forty years ago, when Limits to Growth first appeared, the book aroused an intense international debate, which then blow over within a few years. Today different studies are posing the discussion again. One of the most recent studies, entitled The Limits to Growth Revisited2, takes stock of the copious literature of the last decade to reassert the rightness of the thesis argued in the book. But beyond its recurring re-emergence, The Limits played a crucial role in the growth of environmental awareness on a planetary level. In this essay, we try to describe the reception of the work in Italy between 1972 and 19753.

1. The planetary success of an unusual work

On 12 March 1972, the book The Limits to Growth. A Report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind4 was presented to the Smithsonian Institute in Washington.

The timing was not casual; it was at the eve of two important summits: the Third session of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, to be held in Santiago de Chile in April, and, above all, the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment, that would open in Stockholm at the beginning of June. The report aimed to give world leaders some essential conceptual tools for deciding the future of mankind. The report showed, with a rigorous, clear and attractive style, what the officers, researchers and managers of the Club of Rome had elaborated in the last four years. But the road to reach this agile and brilliant expositive result was long and hard.

The promoter of the initiative, Aurelio Peccei, was an executive with Fiat, with a definitely original story and profile5. He grew up in a socialist and antifascist family, and he studied in Italy and France. He graduated in 1930 in Economics with a thesis on the New Economic Policy of Lenin, and in 1935 he was able to convince Fiat, with which he had collaborated since he was a student, to allow him to go to China. After returning from Asia, he joined the Resistance group Giustizia e Libertà and spent one year in a fascist prison. In the months following the liberation of Italy, he was at the Fiat headquarters, and then he contributed to the founding of Alitalia. Though he was one of the most qualified and creative managers of Fiat, absolutely true to his managerial vocation, his story and profile precluded his climb to the top of the company. Therefore, thanks to his excellent relationship with Vittorio Valletta and, later, with Gianni Agnelli, he succeeded in carving out some interesting space for himself, but always well away from Turin. Competence and cosmopolitan open-mindedness allowed him, step by step, to establish and head up in Latin America one of Fiat’s most successful branches abroad and, in the following years, Adela, a daring “investment and management trust based on the cooperation among different continents” with the crucial contribution of important capital from the United States. Then he restored Olivetti’s budget and industrial policy, and finally created Italconsult, another pioneer “engineering and economic consulting group” for investments in the Third World, with an activity able “to evolve independently from that of the stockholders and their interests”. All these experiences were carried out while his main function in the corporation was the direction of all Fiat operations in South America.

Indefatigable worker, tireless weaver of human relationships – in which he showed an astonishing ease – polyglot, cosmopolitan, curious, open to new ideas and solutions, Peccei decided by the end of the 1950s to dedicate part of his time “to the reflection on human needs and perspectives” in a broader view and with the perspective of doing something concrete in this field. He would write later: “Psychologically, I made almost a complete circle, coming back to some of the ideals and hopes of my youth. However, it took a lot of time before I could satisfy my desire to get involved to contribute to realize them”6. For many years, in fact, Peccei wasn’t able to do more than studying and expounding his points of view during conferences held mainly in Buenos Aires. Due to a series of favourable circumstances a paper of his from one of those conferences ended up in the hands of an English senior officer of the European Productivity Agency, Alexander King7.

From their meeting, on April 1968, was born the Club of Rome, an informal forum of scientists, managers, administrators, transversal to the North Atlantic Treaty, the Soviet bloc and the Third World. After many assessment meetings in different places around Europe, the group found the essential external supports necessary to develop its initiatives, but, above all, elaborated the guidelines of its mission. First of all, the group took note that an entire cycle of human history had ended, that people lived in a new era with indefinite outlines, with plenty of opportunities, as well as huge, original risks. The group also said that ideas, behaviours, and decisions were a reflection of an old and inadequate logic . The progressive accumulation and connection, at a planetary level, of various crises was leading to a global systemic crisis that could certainly be avoided, but only if we acted cooperatively, following new mental and operative patterns, and, above all, promptly.

By the end of 1968, the operative group of the Club of Rome moved in three directions: the enlargement of the group, the study of what was already defined as the “world problematique” and – in particular – the investigation of how to communicate effectively the results of their work to government leaders as well as to public opinion all over the world8. Peccei wrote: “All existing technical means had to be certainly used, but, to have an impact, the message of the Club of Rome had to be presented in a different, imaginative way. I think it had to strike people as a shock treatment9”. After evaluating different options, the choice fell on the analysis and exposition methodology proposed by the American informatics engineer and systems scientist Jay Forrester, worked out specifically in the summer of 1970 by a team from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. That is how the “Report to the Club of Rome” was born, which a year later would receive the title The Limits to Growth.

The choice, though difficult and disputed, turned out to be extremely happy. The book was an easy read – a little more than one hundred pages – clearly structured, well written and, most of all, with lots of clear and elegant graphs. Even if it was a specialized book, about an unusual subject and based on a little known methodology, any person with an average education could easily read it and understand the basic arguments, the data and the proposals.

The research was structured, on Jay Forrester’s suggestion, following the systems analysis criteria that Forrester had already elaborated in his previous books Industrial Dynamics (1961) and Urban Dynamics (1969)10. Systems analysis is based on the study of how some values related to others change in time; we should try to imagine how any of them could vary, if any other changed in a certain way. The analysis could be done with differential equations, trying to predict, for example, how an animal population varies, if, in the same territory, there were other animals, quarries or predators; if the food or the space were insufficient; if there were toxins, etc. The same procedure could be applied trying to relate the business of an industrial enterprise to the market size, the aggressiveness of competitors, the cost of money, the change in consumers’ preference, etc. The solution to the differential equations was difficult, but it could be solved after the availability of electronic calculating machines. We have to think that the powerful (as they said in 1972) calculating machines of MIT, where Forrester worked, were IBM and Digital computers, with one thousand times less computing and printing power than a today’s personal computer that costs a thousand euros.

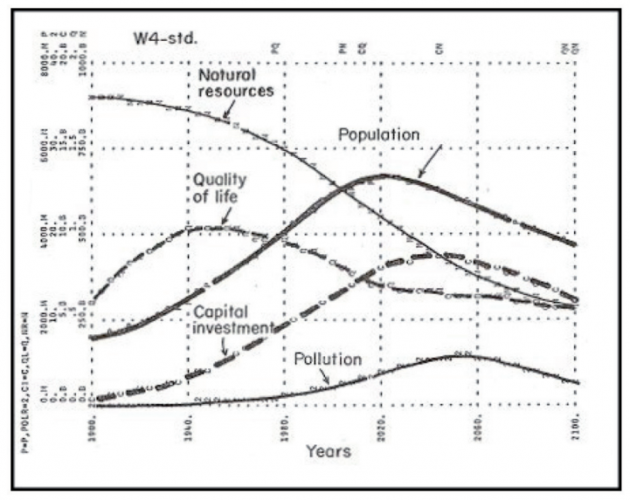

The research investigated the changes in time of five values, between 1900 and a hypothetical year 2100:

- Population, fixed at 1,600 million people in 1900 and 3,500 million people in 1970.

- Food resources, sometimes expressed in kilograms of cereals per person per year, sometimes indicated as “quality of life”.

- Industrialization, sometimes expressed in dollars equivalent to investments per person per year.

- Nonrenewable resources, arbitrary value sometimes determined equal to “100” in 1970.

- Pollution, expressed as multiple of an arbitrary value determined equal to 1 in 1970.

In various texts published, the values were sometimes different. But this is scarcely relevant, because the aim of the study was to identify trends, not to make quantitative predictions. Many critics lost sight of this fact, as they would try to demonstrate the mistakes of the “forecasts” (which they weren’t) of the “curves” of the book.

The interplays can be resumed as follow (using the verbs “to grow” and “to decrease”, because they are physical quantities, which have nothing to do with development, well-being, etc.):

- If the population grows, the demand for food, material assets and goods grows.

- If the demand for food grows, agricultural production must grow.

- If agricultural production grows, the use of fertilizers and pesticides must increase, and soil fertility will decreases due to impoverishment and erosion.

- If soil fertility decreases, agricultural production will decrease, and therefore also the food available.

- If food availability decreases, the number of underfed people or of people who die of hunger will grow, and the quality of life decreases.

- If industrial production grows as a consequence of population growth and the demand for material assets, energy, and goods, the quality of life will increase, but the nonrenewable natural resources available, such as minerals, water and fuels taken form reserves, will decrease.

- If nonrenewable natural economic resources available decreases wars and conflicts to secure the scarce resources will increase, the number of people killed will grow, and the quality of life, as well as population, will decrease.

- If industrial production grows, pollution and environmental contamination will increase;

- If environmental contamination grows, the human health and the quality of life will decrease.

In short, if population growth (which in 1970 was 3,600 million people and grew at the rate of 70 million per year, while today, in 2011, it is 6,900 million and grows at the rate of 70 million per year) continues, diseases, epidemics, hunger, wars, and conflicts will increase. If we want to avoid traumatic situations, the solution, according to The Limits to Growth in its original edition as well as in the versions written twenty or thirty years later, has to be sought in slowing down the world population growth rate, agricultural and industrial production, and environmental degradation; in conclusion, there have to be some “limits to growth” of population and goods and a stable condition has to be reached.

Figure 1. The “basic model” of the simulation made at the MIT, released in the autumn of 197011.

Fully matching the expectations of the authors and the commissioning, the publishing of The Limits represented a global event, more than Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring12, published ten years earlier. Between 1972 and 1974 the book was translated into about fifteen languages13. On March 1974, Peccei presented a list of almost four hundred articles published in the last two years in eighteen countries. It was a largely incomplete list, because there were mainly articles in English, French and Italian14.

What really matters is that, the MIT research report caused out a world controversy to break out, one destined to last until today. It was soon defined as the “Limits to Growth debate”15. To fully understand its importance and significance, it is not enough to trace the main stages and the Italian ramifications; we also have to describe the political and cultural context in which the initiative and the proposal of the Club of Rome emerged.

2. On the origins of The Limits

In the mid-1960s, even if it seems strange, Aurelio Peccei was an accomplished executive: he was not a member of any club of intellectuals or academics, he did not publish articles or books, nor did he have a relationship with institutions and political parties, except as necessary for the accomplishment of his duty. Nothing in his public profile made him similar to an intellectual, let alone to a radical intellectual, even if his personal back story hid a strong political vocation16.

Peccei was a sensible, curious and creative man. In his heart he did not forget the progressive paternal heritage, nor his own past as “giellino”17. When, at the age of fifty, he began to look around to understand how he could be still useful beyond his simply professional horizon, Peccei immediately identified with the issue of the underdevelopment, namely the imbalances between the industrial countries and the rest of the countries in the world. These were the thorniest global problems deserving a solution18. In the following years, Peccei matured and gradually refined his global view, elaborating new issues and dimensions, making it more and more complex. The systemic and global model of The Limits to Growth can be interpreted as a kind of final landing of Peccei’s long personal maturation process, which started in a solitary and rudimentary way and finished in an absolutely conscious and refined collective effort.

An important turning point in this maturation was the 1965 conference held once again in Buenos Aires and once again developing in complete solitude. Out of this conference the Club of Rome originated, as did Peccei’s first book19, thanks to a series of fortunate coincidences. Peccei’s core thoughts were based on a few points: the original and destabilizing nature of current technological progress; its unequal planetary distribution; its always global effects; the risk that a further technological and economical polarization could worsen existing problems; the need to take away from the arms race the role of regulator of technical-scientific progress, and assign it to the solution of the “true problems”; the universal adoption of international cooperation – also with the USSR – as a crucial instrument of the new political situation; the need to adopt quickly fundamental decisions. When Peccei finally talked about the “true issues of the next decade”, he drew up a definitely reformist and social democratic list, but applied on a world-wide scale: survival in the nuclear era, overpopulation, hunger, education, justice in freedom, and a better circulation and distribution of wealth. At this stage, the gaze was entirely directed to the future, and the tone was concerned and full of sense of responsibility. But the emphasis on risks was still contained.

In the years between this third Buenos Aires conference and the emergence of the Club of Rome, other issues were added to the model, existing ones were examined more closely, making the picture more systematic, but also the tone more anguished. The confrontation with researchers, politicians and businessmen from all over the world and the time spent on the global problems allowed Peccei to learn about many other points of view and approaches and make them his, to such an extent that around 1970 the Club of Rome became the point into which all the big issues of the 1960s merged.

When The Limits came out, the book revived in an innovative and effective way some of the subjects popular in previous years, giving an important contribution to some of the most heated debates of that period.

First of all, the book came in the wake of Futures studies20, now rather neglected, but very popular in the 1960s. Futures studies, born in the military field in the United States after the Second World War21, had an international diffusion and gave rise to various public and private initiatives and to studies that caused a great stir22. The elements in common with these studies, which are very heterogeneous, were the observation that technological changes were rapid, the certainty that the scenarios – not only technological, but also socio-cultural – of the near future would be absolutely uncommon, and the conviction that it was necessary to have a new and more sophisticated investigation to face them adequately. Even if the primary intention of Peccei and the Club of Rome was not to swell the ranks of Futurists, there were plenty of points of contact, convergence, and mutual recognition with them. In the varied landscape of forecast study, Peccei discovered strong affinity with the current founded by the French Bertrand de Jouvenel, whose members called themselves “futuribles” and which had many national groups outside of France. The “futuribles” was a moderate and reformist version of Futurist studies. It grew out of the climate of French economic planning of the 1950s thanks to a commis d’état and a rational look at different possible futures, in order to intervene after due consideration. The specialization of the “futuribles” became forecasting and speculative studies, aimed at economic planning23. Peccei and the Club of Rome found in the “futuribles” careful listeners and valid interlocutors, so that in 1970 de Jouvenel24 was co-opted into the Club, while the Italian current25 of the review became an important place to discuss about the issues of The Limits. More in general, the initiative of the Club of Rome and The Limits seemed to be an expression of a cultural climate marked by a strong collective consideration of the future, a consideration that assumed different tones (enchantment, hope, concern, curiosity) and different shapes (studies and plans, political debate, fiction)26. This consideration was related to the observation and perception of a world in a rapid, unpredictable, and – depending on the point of view – thrilling or worrying change due to technological progress. A faster, more “powerful”, almost “magic” world, (capable of an unprecedented, even fantastic, manipulation of nature), more interconnected.

While Peccei’s first reflections were strongly influenced by the 1950s debate on development and the themes of North-South divide, in the Club of Rome these subjects, defined as “the problematique”, were no longer central, even if they were not abandoned. At the end of the 1960s, the main threat to world stability and to the ordered development of humanity were not the imbalances among different areas of the planet, as they maintained their terrific destabilizing potential and their burden of injustice in any case. Instead, there were higher-level issues, much more embedded and dangerous: the nuclear threat, the demographic boom, the increasing shortage of resources and pollution.

Some of these issues had been the object of heated debate for many years, while others were relatively new.

After Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the subject of the nuclear threat never left the stage, always reawakened by the news of missile proliferation and recurring international crises, such as those in 1950 and 1962. Nuclear disarmament became one of the main themes of the movements in the 1960s, especially in Great Britain and in the United States. Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove (1964) gave voice to the fear of nuclear disaster sparked off by almost casual factors. Furthermore, in a period of great collective attention to the issues of development and underdevelopment, the huge public expenditure assigned to nuclear arsenals represented to many people an unacceptable contradiction.

In the developed countries the issue of underdevelopment is expressed – in a still globally “progressive” climate – in terms of backwardness, and especially of hunger: the issue of “world hunger” was never as popular as in these years, and it was the source of two differing theories: one centered on the rhetoric of the“green revolution”, thus on the capacity of technology to eradicate the scourge; the other centered on the impossibility of the Earth to sustain a constantly growing population. Two books published contemporaneously with the founding of the Club of Rome stressed and popularized all over the world the issue of overpopulation, which for some time has been a topic of discussion in politics and in academia27: Famine 75! and, above all, The Population Bomb28.

The last and maybe most important piece of “the problematique” was the environmental issue. The connection between technological progress and consumption growth, on one side, and between the irreversible impoverishment of resources and degradation of the environment, on the other, although well-known and reported in inner circles for a long time29, became the subject of public debate only a few years earlier and aroused heated controversy. The event that brought public attention to the environmental subject happened in 1962, when Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring, with its international success, became the source of an intense debate in the United States and roused the U.S. Congress and the federal authority initial interest30. If the issues of underdevelopment, hunger, overpopulation and nuclear war were themes present from the 1940s, which the debate of the 1960s only amplified, the environmental issue represented something new, and which had difficulty in finding its place and a precise identity before the 197031.

3. Positive opinions and relaunching efforts

In a very favourable climate, the success of The Limits and the Stockholm Conference roused, as the Club of Rome had hoped, an international, incredibly wide and articulate debate that contributed to fixing some standard arguments taken up by many “local” protagonists. In fact, it often became hard to separate the international “Limits to Growth debate” from single national debates.

The most clear and influential distinction was that between “neoMalthusians” and “Cornucopians”, the two extreme wings of the debate. They were well-represented, on one side, by the author of The Population Bomb, Paul Ehrlich32, and on the other, by the economist Wilfred Beckerman33and later Julian Simon34. The latter were protagonists of a long battle against any hypothesis regarding limits to growth. Apart from those radical positions, different and more articulate visions contributed to give voice to the international debate, such as that of Barry Commoner, who recalled the need to revise technologies and consumption and to diversify growth objectives35, or that of Sam Cole and his group at the University of Sussex who emphasized some weaknesses in the methodological choices made by the authors of the report36.

In Italy, the first to deal with The Limits in a systematic way were those who chose to adopt, with some nuances, the point of view of the Club of Rome and to become, in some way, its mouthpiece.

A very early and essential support came – and it could not be otherwise – from the circles related with the future studies, which in Italy had a moderate progressive hue, both in its Catholic (Eleonora Barbieri Masini and Irades, Istituto di ricerche applicate documentazione e studi)37 and liberal-socialist members (Pietro Ferraro). The review “Futuribili”, founded by Ferraro in 1967 in the wake of the French initiatives of De Jouvenel, in April of 197138 published one of the first previews of the Club of Rome’s report and followed the fortunes of the book, publishing often very different points of view on it that were generally sympathetic with the thesis explained in The Limits39.

A temporary, but significant attention was directed, also in 1971, to the first reports of the Meadows working group by the Italian Senate Steering committee on the issues of ecology40. Created on 26 February 1971 by the president of the Senate, Amintore Fanfani, the Committee aimed at producing an analysis of the main environmental emergencies and launching a parliamentary initiative to define a national legislative framework for the defence of the environment. With this initiative, Fanfani, whose inspiration was the entomologist and protectionist Mario Pavan, a former collaborator of his, wanted to bring to the higher Italian institutional level a trend that had spread among American and global governmental élites. In 1968 the U.N. General Assembly planned for 1972 a major global conference on the human environment. Another unexpected change occurred in 1970 with Richard Nixon’s State of the Union speech. On this occasion, the president of the United States, in office for one year, announced with an inspired tone his ambitious and original environmental policies, which, in the following three years, would materialize through a large number of measures, including the creation of the Environment Protection Agency41. A dexterous and open-minded politician, Nixon took note of the growing popularity of the environmental issue, while also betting that focusing on the environment would dull the climate of dissent caused by the ongoing war in Vietnam and growing economic instability. Nixon’s environmentalist swing gave further acceleration to the fast process of popularization of ecological issues. Thanks to his endorsement, a strong push from above added to that coming from public opinion and movements, ending up with the involvement of government élites of the Western countries.

It was in this context that Fanfani resolutely launched the steering committee and scheduled its timetable between the end of February and the end of May 1971. Although his personal contribution was extremely limited42, the politicians and, above all, the experts of the committee worked very hard. They were able to use the initial ideas of The Limits, which were illustrated in detail in the wide introductory report of the president of the Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, Vincenzo Caglioti43. The experience of the steering committee ended up being no more than flash in the pan, however, although it had the merit of preannouncing and anticipating the coming in Italy of a wave that would institutionalize the environmental issues in the first half of 1970s: after the short season of the Ministry of Environment, assigned in 1973 to the socialist Corona, in 1974 the Ministry of Cultural Heritage and “Environment” was created, headed by another intellectual, the republican Giovanni Spadolini. In addition, the first laws against water and air pollution, on the waste disposal, and soil conservation44 were enacted.

More organic and functional was the support to the The Limits thesis coming from that galaxy that could be defined as enlightened bourgeoisie or reformist intelligentsia, of which Peccei himself would be an authoritative exponent. When considering the favour with which magazines such as “Il Mondo” and “L’Espresso” or newspapers as “La Stampa” and “Il Corriere della Sera” received and divulged the contents of The Limits, it is important to remember the public profile of the main promoter of that work. Aurelio Peccei was, first of all, one of the “historical” eggheads of Fiat, esteemed and protected by Vittorio Valletta and later by Gianni Agnelli; but he was also the protagonist of important chapters in Italian entrepreneurial history, such as the creation of Alitalia, the invention of the Italconsult and the rescue of the Olivetti in its most difficult moment. His voice was an independent voice, unclassifiable, but always well-grounded in the Gotha of the big Italian industrial capital and, therefore, deserving of attention to the eyes of the big “bourgeois” press45.

Peccei’s personal authority is not enough to explain the support of the big national press, however. What happened with the “Corriere della Sera” well-exemplifies a more complex and general situation. From the beginning of February 1972, the Milanese newspaper published some articles and opinion pieces in favour of the Club of Rome’s report46. Such attention could only derive from a basic agreement with these ideas, the main reasons for which are easy to guess. The first reason is linked to ownership. Since the immediate post-war period the newspaper has been controlled by a Lombard family, of which an important member, Giulia Maria Mozzoni Crespi, was actively involved in environmental groups. The second reason has to be sought in a sequence of educated and, for that time, open-minded directors who were attentive to changes , such as Giovanni Spadolini, who held the office from 1968 to 1972, and, in particular, Piero Ottone, who directed the newspaper until the end of the Crespi era in 1977. Finally, two excellent journalists with earnest environmental feelings set the tone for the pages of the “Corriere”: Antonio Cederna and Alfredo Todisco. It was a similar situation for popular and important magazines as “Il Mondo” and “L’Espresso”47, bearer of a liberal-democratic progressive and modernizing view.

More in general, we can say that The Limits found the most favourable reception in the lay and socialist reformist intelligentsia. An excellent example of that was the international conference organized at the end of February 1972, thus at the eve of the global launch of the report, by the Unione Democratica Dirigenti d’Azienda-Udda, an organization close to the Italian Socialist Party, directed by Leo Solari, in collaboration with the Fabian Society and the Club of Rome itself48. The conference, held at the FAO headquarters, saw the participation of more than six hundred people. It dealt with all the key elements of The Limits in about forty papers, many of which were presented by exponents of the Club of Rome, (Peccei, King, Thiemann, Pestel), but many others from critics (Sauvy, for example), presenting, in general, an excellent diversification of qualifications, competences and points of view. This experience never occurred again. It gave an idea of the attention paid by the Italian reformist sectors that were involved in the economic planning and in the modernization of the country in a progressive direction.

Apart from the earnest support of the Italian National Appeal of World Wildlife Fund, about which we will talk later, some other favourable stances towards the report were the result of rather isolated reflection, as in the case of the philosopher Emilio Garroni, who published in “Rinascita” an article against the refusal of the PCI to take seriously into consideration The Limits49or Buzzati Traverso himself, whose attitudes represented only a minority of the Italian scientists.

4. Economic discipline, between disorientation and rejection

Even if the MIT report did not use the terminology of economic theory, it inevitably brought to mind two classics of the modern economic thought: An Essay on the Principle of Population (1798-1826) by Thomas Robert Malthus and Principles of Political Economy (1848), where John Stuart Mill expressed his favourable view of the hypothesis of the Stationary State. The ideas of Malthus and Mill, even if famous and taken up every now and then, soon entered into the shadow of heterodoxy: in the case of Malthus, because the historical events seemed to prove his initial assumptions wrong; in the case of Mill, because in time the growth became not only the raison d’être of the capitalism and national economies, but also a phenomenon undoubtedly desirable and “normal”, confirmed – apart from sporadic exceptions – by the empirical experience.

Surely, for all these reasons, but also for a defence of the disciplinary fundamentals fixed by the neoclassical economy, and probably for the adhesion to the logic of business and finance, the Anglo-Saxon economic mainstream was the area from which started the first and harshest attacks on The Limits. In particular, an authoritative, welllistened mouthpiece was the Oxonian Wilfred Beckerman, who from 197250 undertook a dogged and bitter controversy51 against the MIT report, claiming that the lack of growth would imply necessarily “poverty, deprivation, diseases, dreariness, degradation”52, and, at the same time, that market mechanisms would be always able to answer positively to the increase of demand53. In that situation, the voices in the economic field supporting The Limits, or inviting a more careful consideration of it, were altogether few and in general quite marginal, even if we have to add that a rather famous economist who was well-integrated in the academic world had just embarked on a theoretic challenge so radical that the analysis of the Club of Rome paled54.

The circle of Italian economists answered quite late and with a sort of disorientation to the stimulus coming from the society and the world of politics. Only at the end of 1973 did the Società Italiana degli Economisti dedicate its annual scientific meeting to the relation between economics and ecology55 and in Volrico Travaglini’s introductive paper the debate appeared yet rather generic and provincial, the sign of a discipline that, at a national level, had scarce familiarity with the issue. The speeches outlined the framework of an open, not preconceived debate, where the efforts to defend the traditional profile of the discipline faced those that demanded that it be adapted somehow to the new challenges. The composition of guests was interesting (demographers, experts in commodity economics, technologists), but it missed a thread, a unitary inspiration. In fact, a tense tone prevailed, apparently with little interest in the argument, which probably seemed like a foreign object compared to the more traditional subjects. So, the Italian economists seemed to have difficulty incorporating environmental issues into their sensibility and interests, so that the scientific meeting seemed a rather formal tribute to a trendy subject. This attitude emerged also in the treatment given to The Limits: out of twenty-two speeches, the report was quoted only ten times, sometimes in a generic way (Demarco), sometimes in a resolute way (Travaglini, Montesano), sometimes polemically (Gerelli, Bettini) and just in a couple of cases taking it into serious consideration and entering into details (Campolongo, Manfredini).

The most informed and aware speech was Emilio Gerelli’s, the only Italian economist committed at an international level to the issues of the relations between economics and environment56, and who, not by coincidence, would give a tone to Italian environmental economics in the following decades. It was a tone that, from the theoretical point of view would be neoclassical, while firmly in favour of development form the political point of view, and centered on an essentially technical vision of the duties of economy with respect to the environmental issues. According to the international disciplinary mainstream, Gerelli, not by coincidence, had early embraced Beckerman’s approach towards The Limits, and the following year many parts of his paper for the scientific meeting of the Società Italiana degli Economisti would be included, without changes, in the first Italian academic successful work on the relations between economy and ecology, with a chapter that severely condemned the methodology and the conclusions of the MIT report57. Unlike the majority of his colleagues, Gerelli could found his argumentative strength on a clear position and first-hand knowledge of the international literature58.

Outside the academic world, but still in the economic field, the business world seemed to have more clear ideas. The official newspaper of the organization of Italian business (Confindustria), the “Sole 24 Ore”, constantly followed the debate and wrote several times about The Limits, expressing a systematically and structurally hostile attitude. Between April and August 1972, among the many articles about the environment, at least fifteen concerned directly or referred to The Limits, and none of them, apart from a short letter that received a rather polemical answer59, diverged from an extremely defined position: the acknowledgement of the importance of environmental issues, a statement of principle of the entrepreneurs for a solution but, at the same time, the firm rejection of the report of the Club of Rome, with regard to the methodology and the contents60. Confindustria and the “Sole” seemed, in short, to understand, clearly and promptly, the risks for companies related to a possible political success of the thesis of the Club of Rome and devoted themselves to confuting them regularly, in general with moderate tones, but always firmly.

5. The Catholic Church, from the initial interest to the clash on the demographic policies.

In the Italian debate61, the position of the Catholic Church differs for its rather original genesis and developments.

The Holy See also took the environmental issue into consideration quite late, but when it did, it inserted it into an extremely favourable and advanced context, such as that of the Council. Between 1963 and 1967, in fact, Pope John XXIII, Pope Paul VI and the conciliar fathers produced some documents and acts explicitly aimed at making of the Church a protagonist in the great progressive phase of 1960s. Encyclicals as Pacem in Terris (1963) and Populorum progressio (1967), the pastoral constitutions such as Gaudium et spes (1965) and organisms such as the Pontifical commission Iustitia et pax, created in 1967, looked directly at the big planetary problems, such as wars, nuclear proliferation, world hunger and poverty, the imbalance between rich and poor countries, saying that it involved not only the responsibility of Christians, but also that of rulers, companies and scientists.

In these big conciliar and post-conciliar initiatives, the environmental issue was totally ignored, sign of the extreme difficulty in being aware of it and in putting it in a global vision that was wide and ambitious. The 1970s seemed to mark a turning point: in a message read to the FAO assembly on 16 November62, Pope Paul VI finally faced, in a detailed way, the environmental issue, putting it in a wider context, but considering it the ultimate root of all the big problems of mankind. World hunger, the destruction of nature, birth control, arms race, the solidarity among people and generations, and the reorganization of the international trade were the subjects treated in the speech. Despite their apparent diversity, they all were reconnected to a serious root problem that has become dramatic in the past ten years: the nightmare of the biological death of humanity as consequence of the destruction of the natural environment63.

The tone used by the pope was especially clear and showed that he was affected by the maturation of the ecological issue in the collective global consciousness:

It is necessary a radical change in the humanity behaviour, if it wants to be sure of its own surviving; it is not just a matter of dominating the nature: today the human being has to learn to dominate its own supremacy on the nature, because the most extraordinary scientific advances, the most astonishing technical feats, the most prodigious economic growth, if do not go together with an authentic social and moral progress, ultimately turn against the human being64.

The pope’s speech had a great resonance in the ecclesiastical world and contributed to reducing the veil of indifference that for a long time influenced the relations between Church and environmental issues. This appears especially evident if we observe the extremely sensitive antenna towards culture and society represented by “Civiltà cattolica”, the influential review of the Society of Jesus. Until 1969 there was no article, review or note dedicated to environmental issues, while in 1970 there were two articles, a review and a major story: a broad comment by Bartolomeo Sorge on the papal speech. Sorge, who would soon become the director of the review, illustrated the contents of the speech, broadening its perspectives with an updated bibliography at a good specialized level.

Sorge’s article was an important opening towards ecology from a crucial part of the ideological Vatican body, but some less known circumstances made it even more valuable. At the same time the article was published, in fact, Sorge was entrusted to create a closed commission to prepare the Holy See’s participation at the Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm, planned for the spring of 1972. It was the first organization in the Vatican, even if it was informal and temporary, that worked specifically on the environment, and it did so from the beginning with a planetary perspective65.

In the following months, the small commission helped to specify the Holy See’s attitude and structure the papal message that would be read in Stockholm, but also to direct environmental issues in the work of the Pontifical commission Iustitia et pax, an important organization made up of 25 authoritative members from all over the world66. Sorge’s article, the Papal message at the Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm67 and other attitudes are so well articulated, advanced and, in many respects, radical, it seemed possible he could take charge of the ecological issue and that there could be a consequent convergence with the positions of the Club of Rome. But things took another direction: the issue of birth control would shatter the reception of the The Limits and, more in general, of the environmental issue.

Once again, “Civiltà cattolica” well exemplified the guidelines of the Church. Sorge’s pioneer article remained unique: after 1970, the review would write quite regularly about ecology, but never with the same curiosity and sense of urgency. On the contrary, in 1971 the French philosopher and historian François Russo drew a veil of caution around Sorge’s article, recalling the need to distinguish, to avoid emotions, in short, to let the matter cool down and place it at a reasonable distance68. In 1972 – as expected – the articles multiplied, in conjunction with the meeting in Stockholm69 and with the appearance of the debate on The Limits. If the two articles by Eduard Boné on Stockholm are faithful illustrations of the preparation and the progress of the U.N. Conference, half of 1972 the environmental issue in “Civiltà cattolica” was limited to the demographic problem, thanks to three articles by Robert Faricy and one by Pedro Calderan Beltrão70, treated in an extremely analytic way to make clear and give internal coherence to the Church’s natalistic position.

The same happened to The Limits. The report was reviewed, meticulously and in a balanced way, by a young and brilliant collaborator, but very late, in the spring of 197471, mainly to give to Catholics the necessary knowledge to deal consciously with the delicate international year of population and, above all, with the U.N. Conference that would be hold in Bucharest in August. The author would not come back to the subject of environment and resources in 1974, but he would write three intense articles on demographic issues and birth control.

In 1970-71, the Catholic Church was two steps away from including with full rights the environmental issue among the big issues raised by the Second Vatican Council, but the fear of encouraging and leaving space to positions in favour of birth control kept it from delving into the matter and, on the contrary, keeping it pending. It became a topic that had to be faced with extreme caution and only when strictly necessary. And The Limits, with one of its fundamental proposals being the reduction of demographic growth, ended up in limbo.

6. A fine capitalistic plot: the interpretation of the left.

Unlike the academic economists, who did not show any kind of embarrassment in facing the challenge put out by the environmental issue and by The Limits, there was the variegated world of Italian Marxism.

This attitude emerged clearly in two works written few months earlier than the publication of The Limits, which are very important for our article, even if for different reasons. The first work, the proceedings of an ambitious conference that the Istituto Gramsci held in November of 197172, constitutes a representative range of how the different worlds of the left were approaching a partially inedited and, anyway, delicate, matter such as the environment. The second work is an intensely militant pamphlet, supported by information and a full theoretic background. It was radically polemic and uncomfortable, but at the same time hard to pass over in silence. And it would gain popularity and allow a large number of militants on the left to get close to environmental matters. The work was L’imbroglio ecologico by Dario Paccino73. Both works – which do not cite The Limits – present the basis of how the various Italian Marxists will deal with the report of the Club of Rome.

The conference organized by the Istituto Gramsci, cultural arm of the Italian Communist Party , hosted about sixty reports and papers, and was divided into three sessions that showed a clarity of intentions. The papers of the first session treated the canonical issue of “theory”, that is how the environmental issue should be viewed in the light of Marxist theory. It was here, in particular, that Marxists, unlike professional economists, showed their confidence, especially as regards the basic aspects of the environmental issue – the global spatial dimension, the projection in the long term, the systematic nature, the rich philosophical and political implications. These themes were familiar to Italian Marxists, so that they were neither embarrassed nor in difficulty in converting the new matter in the terms of their theoretical apparatus74. Furthermore, the organization of the conference showed how significant segments of the Communist Party and those intellectuality related to it were persuaded that the environment was an urgent political, real priority that had to be taken seriously and put on the agenda of the Italian working class movement. What mattered was, in any case, that environmental matters had to be assumed as imposed by the subjects who bear them, and that they had to be preemptively filtered in the light of the Marxist theory, of the materialist analysis of the scientific and technological changes (second thematic session), and of the needs of struggle and political intervention of the working class movement in its different articulations (third session).

During the conference, the debate was rich and in some moments also conflictual, but an authoritative synthesis came from the introductive report and the conclusions of Giovanni Berlinguer. In the former, Berlinguer begun from the Italian situation, observing how “ecology”, so trendy in the centre-left – Fanfani’s unexpected initiative had come a few months earlier – was demagogic and inconclusive, as it was the economic planning of previous years, even if both would be indispensable for a country as fragile as Italy. Actually, it was necessary to go beyond, especially on a methodological level, taking full charge of the matter of scientific-technological change and the demographic crisis, trying to plan for change thanks to the alliance of ecology, cybernetics and Marxism, the only political thought able to make long-term forecasts. However, that was not enough, because the ecological crisis was deep-rooted in the capitalist mode of production, in the double and parallel distinction between exploited and exploiters and polluted and polluters. Therefore, any project of pure and simple rationalization of the system was doomed to fail. So, the risk of environmental catastrophe was rooted in the evolution of class relationship, and it was exactly this that the “noble protectionists” could not or did not want to see:

Not just that the civilizing function of capital in the domain of nature was running out, but the twilight of the bourgeoisie weighs on the whole planet, threatens to bring about the collapse of the biosphere […] capital universalizes the exploitation, projecting it as the natural basis of life, threatening the existence of future generations75.

Saying that, Berlinguer had to admit implicitly that besides a serious planetary ecological urgency, there was an “ecological issue” that expressed itself in different ways. It was necessary to distinguish the reasonable aspects from the ideological and propagandistic ones, a matter that, while involving growing sectors of world public opinion, remained largely unknown to the Italian and international working class movement. This was a serious delay, because it was puerile to think that the pure and simple instauration of a socialist regime could solve by itself environmental issues and because science offered to the working class movement fundamental weapons to show better the incurable conditions of the capital. This encounter between science and the working class movement – opposed until then – had to be rethought and favoured at any cost. In his conclusion, Berlinguer raised his sights. The working class movement did a lot on a planetary level for peace and internationalist solidarity: would it be able to do the same for the environment, especially if “the ecological policy is not just a new problem, but a new dimension of many problems – maybe of all of them – of our politics”76? This appeal to put the environment at the centre of the communist project did not exclude the dimension of the contingent, of immediate action: if it was clear that the “conscious socialization of the biosphere” and the “scientific planning of resources” were possible only in “an international system of socialist relations”, it was necessary to begin here and now. We could not wait. From here on, the need for struggles, even the partial ones: “in every field are possible partial results, relations among states are necessary, legislative compromises are inevitable”, but having a clear final goal and subordinating everything to it.

This articulated, all-embracing attitude, one that was also aware of nuances, mirrored the theoretical ambition and the culture of “struggle and government” of the PCI and the trade unions in the early 1970s. It also gave voice to the attitude of the “official” Marxist left towards the emerging environmentalism and the publication of The Limits.

Paccino’s book, in spite of its heterodoxy and the transience of many of its parts, can be considered one of the most ambitious and best works ever published in Italy on environmental issues77, and it is definitely and consciously unilateral. The environmental issue is crucial, and not just today. It points out the history of the relationship between man and nature, a history widely explored in the book; the environmental crisis is a fact; but the actual “ecology” is a capitalist ideology. More precisely, it is “the umpteenth deceit of the capitalist bosses to gain acceptance for the degradation imposed by profit and to earn from the anti-pollution industry”78. The PCI reformist perspective, as illustrated by Giovanni Berlinguer during the Gramsci conference79, is necessarily disastrous because it does not postulate the abolition of private property. Berlinguer wanted to underline the delays of the Italian and international working class movement, negated the opportunity to consider the Soviet Union as an exemplary environmental operating model and judged naïvely the attitude of those who think that the coming of socialism would automatically bring the solution to environmental problems. Paccino, on the other hand, pointed to the China of the Cultural Revolution as a model to follow and the choices made by the Maoist leadership after Liu Shaochi ousting.

For what concerns us more closely, it is interesting to note how in Berlinguer’s paper and in Paccino’s book, as well as in the majority of discussions during the Gramsci conference, there was a great defensive concern. It seemed clear to everyone, even if the subject was often approached in an ironic and compliant way, that the workers and their organizations were facing a challenge that concerned them both as victims of pollution and revolutionary subjects. At the same time, they struggled to make it their own, but they were also chasing the initiative of other subjects, even that of their class enemy. Richard Nixon’s State of the Union speech in January 1971 and Fanfani’s environmental push the following spring represented two real spectres that recurred constantly during the debate as examples of bourgeois mystification, but also as a silent indictment of their own inadequacy and of political threats not to be underestimated.

It is no accident that both Berlinguer’s paper and Paccino’s book dedicated important parts to a detailed taxonomy of the different positions towards ecology. Paccino used the political-spatial metaphor to define the position of the ideological alignment80: an inter-classist, scientific and technocratic centre à la Nixon; a left represented by the aristocratic associations – WWF and IUCN above all – that wanted nature sanctuaries, disdained liberalism and Marxism, origin of the hated mass consumption, and preferred bears to men; a reformist left not too far from Nixonians, that stressed the possibility of reconciling ecological and development demands; and a radical left, represented by romantic catastrophists, populationists, and, after all, antihumanists. Berlinguer’s classification was inspired by the same political concerns, but, since it was not conceived for polemical aims, was more articulated and nuanced in its judgment. In fact, trying to distinguish in the various positions the serious and common elements from those simply propagandistic and irrational, Berlinguer listed six positions: that of the Catholic world, of the catastrophists, of the Neo-Malthusians, of the anti-technology romantics, of the anti-pollution industrialists, and finally the Nixonian.

In Paccino, as well as in the different papers delivered at the Gramsci conference, some basic criticisms recurred constantly: the bourgeois ecology had an undoubted profiteering side, because there was an evident will to sell new anti-pollution technologies; its institutional declination (Nixon, Fanfani) was basically propagandistic, pretending to define all victims and all responsible in equal measure and to divert attention from destabilizing issues, but it had also an authoritative connotation, because basically technocratic; catastrophism, in essence, was passive and did not take in account the potential related to the political centrality of the masses; finally, the stress on population control – a statement clearly derived from Malthusianism – was an evident declination of neocolonialism81.

Thus when the Club of Rome’s report appeared on the Italia media and political scene in the spring of 1972, the reformist left and the revolutionary left had some consolidated analytic filters with which to judge the work. And the condemnation was, in general, without appeal.

The entire PCI press rejected the thesis of The Limits, without going into details or publishing a specific review. In two articles in “l’Unità”82 that commented on the conclusions of the Stockholm Conference, Cino Sighiboldi reduced The Limits to the zero growth theory, denied the efficacy of the methodology adopted by the Meadows, lined up with whom, like Indira Ghandi, thought that the proposal of the Club of Rome was a manoeuvre of the international industrial powers and big companies to perpetuate the subjection of the countries of the South of the world. He also accused the authors of technocratic authoritarianism. In spite of the fine and worrying distinctions contained in his paper a few months earlier, Giovanni Berlinguer wrote off, in a very sharp and contemptuous tone83, the initiative of the Club of Rome in two articles in “Rinascita”84, without getting into the heart of the matter, underlining, in particular, the Neo-Malthusianism of the report. This rough abruptness aroused some embarrassment, wellexpressed by a long article in “Rinascita” by the philosopher Emilio Garroni, who went into the details on The Limits, criticizing Berlinguer and the PCI’s narrow-minded attitude85. Significantly, nobody replied to Garroni’s articles, even though it was received with words of appreciation. In the articles of the communist press, the works of the Istituto Gramsci’s conference were regularly recalled to signal the PCI’s dynamism on the environmental issue. , but it strikes the gap between the problematic nature of many of the conference presentations, in particular Berlinguer’s keynote speech, and the schematism, somehow coarse, of the articles, as if the propagandistic needs and the political line would prevail against the articulated argument. We should not be surprised, then, that the final wish of the Gramsci conference “to make environmental policy one of the subjects of the current debate and – why not? – of the 1973 election”86 became a dead letter in the PCI, at least until the 1979 national conference, when, in a rather mild way, the environmental issue was inserted for the first time in the party official documents87.

In the so called “new left”, the reception was substantially similar, even if there were attempts at less-hurried approaches88, at least at an analytic level. This was the case of a long and reasoned article by Marcello Cini on “il manifesto”,89 which invited the reader to observe with attention and without prejudices the analysis of the report. But at the end he wrote a sentence similar to Paccino’s style:

It is not following the suggestions of a computer that the course of history changes. The transformation of the society in the class struggle neutralizes Cassandras’ previsions. It is fighting against the capitalistic organization of work that the worker fights the most valuable – the only really valuable – struggle for ecology.

Equally well-argued and detailed was an essay by Giovan Battista Zorzoli, published in the review “Fabbrica e stato”. Zorzoli entered into the heart of the work, showing a good knowledge both of its social-political (the work of the Club of Rome) and methodological (the technological forecast study, the work of Jay Forrester) origins. The Limits was important for its methodological genesis. The report represented, in fact, a “third level” in technological forecast, which was the “discipline that for more than a decade provided the tools to coordinate technological development”90. Facing a structural crisis in capitalism that could assume catastrophic dimensions, the bourgeoisie provided itself with “an alternative, highly demanding, and at the same time articulated and detailed, project”, giving to itself “a hegemonic potentiality where until now it was more exposed towards the Marxist theoretical elaboration”. The Limits is read by Zorzoli as a clever and articulated move of international capital to get over its own contradictions, justifying theoretically, thanks to it, the stagnation phases, giving new legitimacy to the objective of a dualistic development and strengthening the demand of technologies for environmental clean-up. From this kind of reading came the need for “blunting” this “weapon too dangerous in the hands of the bourgeoisie”, pointing out the limits as the absence of an analysis of the causes of the current development model, the ideological nature and the illusoriness of many suggestions. About this last aspect, Zorzoli ended like Cini, showing that the necessary ban on chlorinate pesticides in agriculture could not be obtained through technology, but “through the radical transformation of society”.

The article was intelligent and subtle in its argument, careful about the specific contents of The Limits and, most of all, careful not to distort them. It went beyond simple condemnation. It took the report extremely seriously , because it was “another challenge of the bourgeoisie”, maybe one of the most radical and dangerous. Zorzoli represents a good example of a common attitude of the left, based on a theoretical construction intimately coherent but also influenced by a conspiracy theory not confirmed by facts. Only a few people in the Italian Marxist left in the early 1970s were able to see the deep difference between Aurelio Peccei and the capitalist “big brother” dear to the imagination of many.

A separate chapter, quite difficult to classify in the standard left, is represented by the position of the Italian appendix of the European Labour Council of Lyndon Hemyle La Rouche. La Rouche91 was born in 1922, Quaker by family tradition and Trotskyist from the 1950s. From the time of his first appearance on the American public scene at the end of 1960s, he became an original synthesis of traditional organizer and Marxist theorist and the typical “guru” founder of religious sects. His National Caucus of Labour Committees, founded in 1969, is an organization of the extreme left – even if rather atypical – completely subordinate to the charismatic figure of its leader, intensively faithful, designed to guarantee large financial flows towards the centre, where militants are subjected to psychological conditionings and the unchallengeable decisions of a hierarchy that operates through a system of internal espionage. A nimble manager, Larouche gave an international breadth to his organizations in the early 1970s, creating in Europe the European Labour Council, with the Partito operaio europeo as its Italian branch. Around these political groups there was an intricate and opaque galaxy of cultural organizations (New Benjamin Franklin House, Executive Intelligence Review, Schiller Institute) and reviews. La Rouche’s followers, many of them active in Europe, especially in the second half of the 1970s, were separate from the European and national parties. They founded some reviews with a remarkable number of pages, a regular periodicity and a decent diffusion. The Partito operaio europeo publication was “Nuova solidarietà”, a fortnightly review characterized by the ongoing announcement of catastrophes and/or triumphal successes in the immediate future; the constant appeal for the creation of an international bank for development and a debt moratorium; scarce attention to real movements in society and politics; the exaltation, to an environmental level, of Soviet technology for nuclear fusion, and the certainty of imminent great plagues; firsthand information, often confidential; virulent and obsessive attacks on people and institutions such as the Rand Corporation, the CIA, NATO, Rockefeller, Kissinger, Brandt, Palme, Agnelli, the leadership of the PCI and, in particular, Giorgio Amendola, and finally the “Maoists”; the conspiracy theory – typically American – that leads to affirm that even the earthquake in Friuli was caused by NATO; the exaltation of the Mancini-Andreotti-Cefis axis, the only able to contrast the other – this time baleful – axis represented by Agnelli and the PCI leadership; a very strong pro-Soviet attitude and a rather strong (even if not constant) support for the parties most faithful to Moscow, with a special preference for the Portuguese communist party of Alvaro Cunhal; the desire to overthrow the PCI leadership and set up a new one.

In our case, the remarkable aspect of the works and propaganda of the Larouchists is the constant attack on the Club of Rome and on The Limits to Growth, interpreted as a dark message from the oligarchs Rockefeller or Agnelli. Some of the criticism made by the Italian Marxist left of The Limits were brought to the extreme until becoming a caricature, both for the subjective description of the promoters of the book and for the idea that it was a conspiracy against poor countries. On the other hand, a relatively original element was the criticism the idea of physical limits to growth, which was in contrast with the exaltation of Soviet nuclear technology for fusion, able to guarantee in few years unlimited energy.

The radically hostile attitude of the Partito operaio europeo and “Nuova solidarietà”92, little known realities at that time that soon disappeared without a trace in the Italian political landscape, to The Limits could be part of a coloured chapter of the history of the 1970s. But some of the protagonists of that season – in keeping with the evolution showed shortly after by La Rouche – embraced positions of right-wing environmental negationism, when in Italy this current was yet at its beginning. The president of the Partito operaio europeo in the 1970s, Marco Fanini, wrote for “Nuova solidarietà”, as did Giuseppe Filipponi, who was also was a candidate in the 1976 general election. In 1988 they collaborated on the book La congiura ecologista. Guerra irregolare dell’oligarchia malthusiana del Kgb93, together with Antonio Gaspari, who later became one of the most active member of the traditionalist catholic anti-ecologism94.

7. The oscillation of the young Italian environmentalism

The reception of The Limits to Growth by the new Italian environmental movement basically repeated the cultural fault lines described above.

In the early 1970s, it was still in a consolidation phase. After the exhaustion in the 1930s of the first protectionist wave formed between the nineteenth and the twentieth century95, Renzo Videsott’s attempt to create an environmental association failed soon after the end of the Second World War.96 The attempt by a group of young people from the association Italia Nostra to give an environmentalist turn to the association also failed.97 It was only in the first half of 1960s that, with determination but also with hard work, modern Italian associationism with a national wide breath got off the ground. In 1965, a group of enthusiasts created the Lega nazionale contro la distruzione degli uccelli-Lenacdu, which was the first core of the future Lega Italiana per la Protezione degli Uccelli-Lipu; in 1966 the “Gruppo Verde” of Italia Nostra, without further delay, founded the Italian National Appeal of World Wildlife Fund. It had only a few members but clear ideas and great ambitions98; in the same period, Federnatura, which for years operated only in provincial areas, saw a re-launching phase99. But we have also to remember that, in the wake of some shameful events, such as the speculative attack to the national parks and the penetration in Italy of the ideas and stimuli from the American “ecology spring”, some big names in the Italian press (especially Antonio Cederna, Alfredo Todisco and Mario Fazio) dedicated themselves to the examination of the environmental matters100.

In spite of this ferment, at the beginning of the new decade, Italian associationism and environmentalist culture were rather weak. The WWF, which represented the great Italian novelty for its effectiveness and visibility, had only a few thousand members101 and a few local offices. Meanwhile, the environmentalism of the left began to find the distrust of the PCI and the extra-parliamentary groups.

In theory, the WWF could have had some difficulties in dealing with issues such as those raised by the Club of Rome, because it was born with a clear protectionist mark, interested first of all in preserving threatened species of flora and fauna and places of special naturalistic value. The nucleus of young people who gave life to the group came from the politically complex reality of Italia Nostra and was of the reformist culture typical of the first centre-left. All of its members were also members (or were very close) of the Partito socialista and Partito repubblicano, the two parties committed to the modernization of the country, as embodied in economic planning. It was this opening of horizons that made possible in 1971 an official stand of the association regarding the risks related to the overpopulation, as seen in two unusual editorials in the group’s publication,102 and which the following year – soon after the publication of The Limits – induced the national committee to approve a resolution in which the association recognized “in the basic thesis expressed by the Club of Rome a correct analysis of the planetary situation, adopting it [the report] as text of diagnosis and therapy for its action”103. The WWF Italy had clout on the national debate. In 1972 the association enjoyed a growing popularity, beginning an organizational rise that would bring it in few years to triple its membership 30,000 in 1976.104 It had the important support of the “Corriere della sera” of Giulia Maria Crespi, and saw its fame paradoxically increase also thanks to the caustic attacks such as those contained in Dario Paccino’s successful book L’imbroglio ecologico. Many people, among them many young people, came closer to the MIT report thanks to the WWF.

The enthusiastic reception of The Limits from the top circles of WWF Italy could in part be ascribed to the positive reception of the book by the reformist liberal-socialist. But the rejection or, at least, the strong distrust from the rising environmentalism of the left – in this phase rather very fragile and in a minority – is mostly due to the rejection showed by the Marxist culture. The first important attempts at synthesising environmentalism and left militancy came from the journals “Ecologia” and “Natura e società”.

“Ecologia” was a brave and somewhat paradoxical experiment made by a young, left-wing geographer, Virginio Bettini, who was able to convince the publisher of a technical review of the chemical and energetic field (“Acqua e aria”) about the potential of a format directed partly to the old readership and partly to the new, growing readers interested in the environment. The review, the first issue of which was published in May 1971, presented a strong discrepancy between its contents, extremely radical, and the advertisements, mainly from companies that were major polluters and often an expression of big capital. On top of this, Bettini called to the editorial board and the staff anybody who worked in the environment, without making any distinction: industrial engineers, academics, journalists, representatives of environmental associations, and militants, even very young ones. This generous attempt at “filling” the review while ignoring the need to give it a homogeneous outline brought it big and representative names, but also generated a true cacophony and even some violent internal clashes. In such a confused context, the political and theoretic heart of the journal was not, as was usual, in the editorials and in the fuller essays that reflected the heterogeneity of the editorial board, but in the final columns, edited by Bettini and by his close collaborators, which were usually high-quality, coherent contributions.

It was here that the choice to favour the outline of the biologist Barry Commoner about the relationship between population and pollution on a global scale emerged. Commoner, with whom the editorial staff had a direct relationship that was consolidated through the participation at the U.N. conference in Stockholm in 1972, was an extremely prominent figure in the American environmentalism and author in 1971 of a widely known work that contrasted the thesis Paul Ehrlich put forward three years earlier105. Commoner thought that the vision supported by Ehrlich and many others, which placed overpopulation at the centre of the environmental crisis and called for drastic birth control, was coercive, anti-democratic, and above all off target. Population and consumption were undoubtedly important components of the ecological crisis, but the decisive factor was the bad use of the technology, due to the logic of robber-baron-type capitalism. In consequence, instead of proposing – or, to be more precise, imposing – antinatalist policies with a taste of neocolonialism, it was necessary to change the collective ideals and objectives, review the technological choices and be more disciplined about consumption and waste106. In a review of The Closing Circle, it was immediately recognized that the harsh controversy between the two researchers obscured their respective positions, which not so far away from each other. Both “admit that it is necessary to slow down the growth of population and consumption, and to direct the economy and technology towards social purposes aware of the environmental problems”107; the difference is, in substance, that Ehrlich underlines mainly the urgency of limiting births, while Commoner insists more on a change in technology and consumption. This acknowledgement persuaded some exponents of “Ecologia” to receive with great attention – even if tinged with certain suspect – The Limits.108 But a drastic and simplified version of Commoner’s thesis became for many people the key for rejecting – without entering in to the merits – the analysis and proposals made both by Ehrlich and the Club of Rome109.

This was primarily true for the Marxist left110, but it was also the same for ecclesiastical circles111 and for left-wing ecologism. In spite of the authoritative presence of Nebbia and Pratesi in the editorial board of “Ecologia”, the review of The Limits112 arrived very late and it had a rather low profile, assigned to the self-managed supplement “Denunciamo…” edited by the young members of the Movimento ecologico of Milan. The review wrote off in a rather hurried and broad manner the report of the Club of Rome, using many arguments typical of the Marxist political journalism, accusing it every now and again of technocratic Miraclism, unforgivable analytic gaps, Neo-Malthusianism, complicity with the “imperialistic attempt to control raw materials”, and finally of a suspicious political ingenuity. The argument ended with a reference to The Closing Circle, where Commoner wrote: “It is not about stopping development, but to halt it where it is injurious”.

In the early 1970s “Natura e società”, as well as “Ecologia”, were heterogeneous and vivacious places for discussions. “Natura e società” was the creation of the botanist Valerio Giacomini, elected president of Federnatura in 1968, to give to the association a more political connotation and make it more aware of the relationship between environmentalism and big social issues. In 1970, the association approved the foundation of the review and Dario Paccino, who came from the Touring Club Italiano113, was nominated director. “Natura e società”, as well as “Ecologia”, contained different spirits and sensitivity: the progressive, but very radical outline of Paccino and the moods of the rank-and-file, represented by associations and local groups, which did not always agree with the editorial slant. This would slowly lead to the end of this set up114. For some years, “Natura e società” was a combative and avant-garde review, able, perhaps more than the others, to slug it out in the national and the international debates. Although it was mainly focused on the Italian events, new foreign books were reviewed; The Closing Circle had a long review and a whole number was dedicated to the Conference of Stockholm. For this reason, it is hard to believe that it was a coincidence that the report of the Club of Rome was never taken into consideration, neither incidentally or indirectly115. That was maybe Paccino and the editorial staff’s way to suggest the scarce importance with respect to a serious and coherent environmentalist debate on a book surely well-known by the readers of “Natura e società”.

8. The indifference of the institutions after the short attention of Fanfani.

In Italy, the positive attention from the lay press, the promotional efforts of the publisher Mondadori, the intrinsic quality of the work, the contemporary international success and the great relevance of its subjects and arguments contributed to make The Limits to Growth a best seller. As we saw, the Italian debate on the book was not less vivacious than anywhere else, and in this sense the members of the Club of Rome could be satisfied: the goal of making known their thesis and opening a debate was largely achieved. But this goal was just the first step on a necessary as well as long and demanding path. The next immediate steps had to be the moulding of an aware and active public opinion and the direct involvement of governments. Here the success was mixed and, most of all, harder to quantify, even if in the following years there would be several good signs.

The surprising and strong endorsement116 of the Club of Rome’s thesis in February 1972 by the vice president of the European Commission (who became president in the following month), the Dutchman Sicco Mansholt, was perhaps the biggest sign of attention from a statesman and contributed strongly to the debate. The following years would see some other important support some extemporaneous, others more systematic, from the likes of Valery Giscard d’Estaing, Olof Palme, Bruno Kreisky, and Pierre Trudeau.

With the words of one of the most active member of the Club of Rome:

Beyond the meetings of the Club of Rome itself, and the projects and publications it has sponsored, Aurelio Peccei and Alex King travelled literally millions of miles visiting heads of state in practically every country in their efforts to encourage a rational, cooperative approach to a global future. They were persona grata in every capital, whether East or West, North or South. Several meetings of heads of state of more than 20 countries (excluding the super powers) with a few Club of Rome members were held, notably in Salzburg (1974), Guanajuato (1975) and Stockholm (1978). Successive meetings have shown increasing awareness of the problems on the part of the heads of state and, depressingly, increasing pessimism regarding the feasibility of addressing those problems effectively within the constraints of political institutions117.

In Italy, in spite of the early attention showed by Fanfani in the spring of 1971, the excellent selling of The Limits and the constant attention given to it in the press, the world of politics and institutions seemed substantially impermeable to the stimuli of Peccei and the Club of Rome.

Eleonora Barbieri Masini would remember later: