By Alan AtKisson

Alternatives and Complements to GDP-Measured Growth as a Framing Concept for Social Progress

2012 Annual Survey Report of the Institute for Studies in Happiness, Economy, and Society — ISHES (Tokyo, Japan)

Table of Contents

- Preface

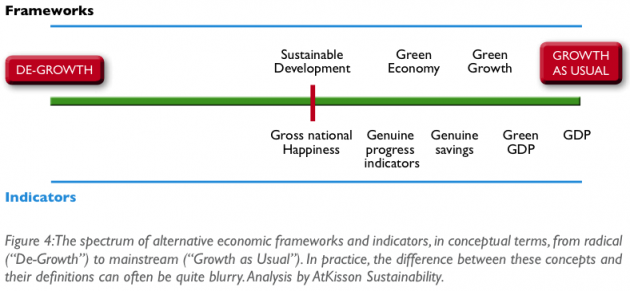

- A Note on Sources and References

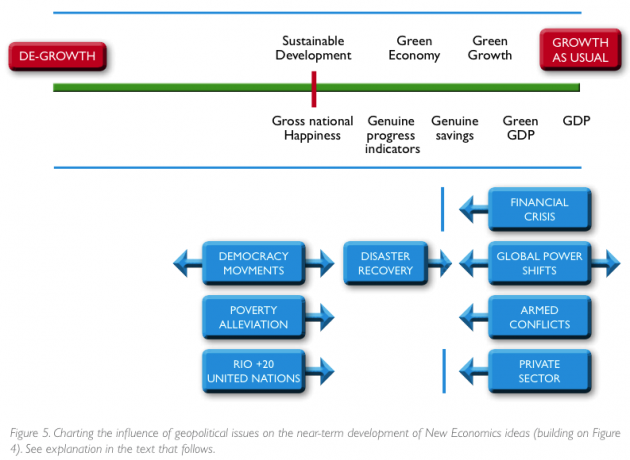

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: The Historical Foundations of Economic Growth

- Chapter 2:The Rise (and Possible Future Fall) of the Growth Paradigm

- Chapter 3: The Building Blocks of the Growth Paradigm

- Chapter 4: Alternatives to the Growth Paradigm: A Short History

- Chapter 5: Rethinking Growth: Alternative Frameworks and their Indicators

- Chapter 6: Looking Ahead: The Political Economy of Growth in the Early 21st Century

- Chapter 7: Concluding Reflections: The Ethics of Growth and Happiness, and a Vision for the Future

- References & Resources

Dedication

This report is dedicated to the memory of Donella H.“Dana” Meadows (1941-2001), lead author of The Limits to Growth and a pioneering thinker in the area of sustainable development and ecological economics. Dana, throughout her life, managed not only to communicate a different way of thinking about economic growth and well-being, but also to demonstrate how to live a happy and satisfying life as well.

Preface

“Life Beyond Growth” began as a report commissioned by the Institute for Studies in Happiness, Economy, and Society (ISHES), based in Tokyo, Japan. The initial assignment came at a time (early 2011) when Japan was wrestling with serious economic challenges, including a decade of stagnant economic growth, an aging demographic, rising unemployment, and an industrial base increasingly dependent on the overconsumption of imported resources. These unsustainable economic trends created a compelling basis for a shift in emphasis from traditional industrial growth-based planning toward a new vision of social progress based in personal and social happiness and well-being. From the standpoint of early 2011, it seemed possible that Japan, among other countries, was on the brink of “switching” from being a growth-centered society, to being a well-being-centered society.

The first draft of this report was completed in time for the launch of ISHES, held in Tokyo on 4 March, 2010. (Attendees included a number of government and industry representatives, including an official responsible for developing Japan’s economic growth strategy.) The purpose of the report, at that time, was to provide a quick survey of the state of the field for the new Institute, as an input to its strategic planning and programming.

I was honored to provide a keynote presentation for the ISHES launch event, and an initial summary of findings formed the core of my opening presentation for that event, under the title “37 Questions about Happiness, Economy, and Society… and One Statement.” The “statement” was a quotation by John Maynard Keynes, from his essay on Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren (1930), about the coming economy of leisure.1 The emphasis on questions — 37 of them! — underscored that the important issues being explored by ISHES were very much open-ended, under examination, and far from resolved.

One week later, on 11 March 2011, the depth and breadth of those unresolved questions expanded enormously. In the series of events known in Japan as the Tõhoku earthquake and tsunami, or more colloquially as “3-11”, Japan suffered its worst natural disaster in modern history, compounded by the world’s worst nuclear disaster since Chernobyl. As of early 2012, Japan was still recovering from the combined effects of the earthquake, tsunami, and destruction of three nuclear reactors, which claimed approximately 20,000 lives. the full social and economic impact of these events will not fully be known for many years. There is no doubt that the events of 3-11 have already transformed Japanese society. To a significant degree, they have changed the rest of the world as well, especially as concerns the future of nuclear power.

The enormity of these events, combined with the devastating losses suffered by the Japanese people in terms of lives, livelihoods, and national economic prospects, obviously had a profound impact on the writing of this report. While the facts have not changed regarding what is happening globally in the area of new approaches to economic growth and its alternatives, the context around those facts shifted dramatically during 2011 — and not only in Japan. The year 2011will be recorded in history as a year of momentous changes in many parts of the world, from the upheavals in the Arab countries, to the droughts and famines of Africa, to financial turmoil in both the Eurozone and the Dollarzone.

These changes in the world both delayed and caused significant changes in the approach of this report, as well as reconsiderations about its purpose and central message. In a world where people are suffering the terrible effects of disaster, compounded by painful declines in economic security and/or the loss of their economic livelihoods, it would be difficult, if not ethically inappropriate, to argue against economic growth in a categorical way. In recovering from earthquake, or avoiding famine, or placing a state’s finances on a stable platform, economic growth – of a specific kind – is seen as an absolute necessity.

But what kind of “growth” is necessary?

This question provides a bridge to the original purpose of this report: to survey the current “state of the art” regarding the possibilities for Japan – or any country – to create an economy of well-being rather than an economy based on unending economic growth. On a finite planet, where all life (including human life) is dependent on finely tuned ecosystems, unending physical growth is categorically impossible. However, the quest for human development, happiness, and well- being presents limitless possibilities.

Happiness and well-being, after a century of being excluded from serious consideration by the mainstream of economics, have emerged in recent years as serious topics of economic debate and policy innovation in diverse countries and across the spectrum of ideological opinion. It is hoped that this report will help to accelerate further change in this regard.

In light of the events of 2011, of course, accelerating a sustainable social and economic recovery, in Japan and elsewhere, is now also part of the aim of this compendium of ideas and policy alternatives.

The information in these pages has been gleaned from around the world, and the ideas reported on here are the result of decades of thinking and experimentation, by many people in many cultures. While the experiments are still in progress, it is already possible to see a new framework for economic goal-setting emerging, one that has the potential to reconcile the need for economic growth (where it is truly needed), the desire for human happiness and well-being,and the boundaries of what the planet can sustain. As such, the vision offered at the conclusion of “Life Beyond Growth” offers the possibility that we might find, together, a realistic path forward to a sustainable future, not just for Japan, but for the world as a whole.

Structure of the Report

“Life Beyond Growth” is intended to be an annual publication that will update decision makers and members of the general public on the status of the current debate, as well as policy shifts, related to the issue of economic growth, happiness, and well-being.

For this first edition, however, we provide a more detailed historical background. The report begins with an overview of the rise of the “growth paradigm” in modern industrial times, as well as the more recent rise of challenges to that paradigm. We gather all of these challenges, new frameworks, and alternatives to the dominant growth paradigm under the overall heading of “New Economics.”

Following that historical review, the report provides, in guidebook format, a current summary of the specific frameworks, concepts, and methodologies – one is tempted to call them “brands” – under which New Economic thinking is most prominently promoted. It also describes the indicators (measuring systems) that help to make those frameworks tangible as well as policy- relevant. In some cases, the framework and the indicator are essentially identical – that is, the new indicator defines a new economic framework, and vice versa.

The final chapters provide a more speculative look ahead, including thoughts about how geopolitical factors are likely to influence the development of these ideas in the near term, and how the disparate streams of alternatives to traditional economic growth are likely to sort themselves out into a more coherent river of ideas for change. The last chapter also includes a reflection on the ethics of growth and happiness, and a proposal for an integrative framework that marries the recent trends in “Green Economic” thinking with the rise of “National Happiness” indicators worldwide. This marriage of concepts has the potential to provide the world with a clear vision of what must be achieved in the coming decades, as well as some sense of how to get there.

The world’s choices about how it pursues economic well-being are, at bottom, ethical choices. Indeed, one of these choices has to do with how we view choice itself: Are we encoded by our biology to always want growth, thus rendering “New Economics” a kind of evolutionary sideshow? Or can we choose how we relate to the essential business of “making a living” on this small planet, which we share with so many other living things?

Is there “Life Beyond Growth”? In the end, this question cannot be answered, definitively, except perhaps by trial and error.This report is offered in the hope that our attempts to find the answers will lead to a satisfying life for all, on a vital and diverse planet, and that we can avoid as many errors as possible along the way.

Acknowledgements

While I serve as lead author, this report would not have been possible without the excellent work of two excellent writers/researchers recruited for this project, Hal Kane of San Francisco, and Catherine Kesy of Luxembourg. Diana Wright of Vermont also provided invaluable editorial input.

Together we pored over the contemporary literature on the limits to growth, the limitations of economic measurements, current alternatives to “growth” as a proxy for overall social progress, and the emerging art and science (for it is very much supported by science) of happiness economics, among other topics. We adopted the “less is more” approach to the report itself: our goal was to provide an easy-to-read, engaging introduction to these topics, and a portal into further reading and web surfing into this rich and diverse family of concepts, frameworks, and measurements.

To Junko Edahiro and ISHES, we express our thanks for this wonderful assignment.We offer our apologies for any lacks, flaws in design, or errors it may contain. And we hold out our highest hopes for the success and impact of Institute for Studies in Happiness, Economy, and Society.

And finally, to the people of Japan, we extend our great hopes for continued recovery from the terrible events of March 2011, and for a brighter, more sustainable, and happier future.

– Alan AtKisson

Stockholm, Sweden

31 January 2012

A Note on Sources and References

This report draws on a wide variety of scholarly books and articles, policy documents, news reports, organizational websites, and online encyclopedias, as well as many hours of participation in conferences and seminars on topics related to economic growth and its alternatives. Often an observation or reflection noted herein is actually a synthesis, drawing on several such sources. In the age of the Internet, it makes little sense to catalog each and every source when most facts can more efficiently be checked (using multiple sources) by a quick web search. Moreover, since I have been working in this field for over two decades, it is sometimes difficult to identify, or even remember, the exact relevant source for a reflection that is the product of years of observation.

Instead, I have opted to focus our cataloguing of references on those sources that are very specific, that are current “key sources” in this field, and/or that would not otherwise be easy to identify or to find. For example, we do not list references to explain the origin of the word “Anthropocene” in the opening paragraph of the first chapter, for while this term may not familiar to all readers, it is easy to find key references via the Internet. On the other hand, when the report is drawing on specialist publications, very recent news articles, presentations at recent conferences, or personal communications with experts, we have endeavored diligently to catalogue these sources.

A. A.

Introduction

Can humanity as a whole be happy and satisfied without destroying the natural systems on which we depend? This question began to haunt the minds of researchers towards the end of the 20th century. Now, in the 21st century, it has become the most urgent question of our age.

Scientists increasingly refer to this period of time as the “Anthropocene,” by which they mean the time in Earth’s long history that is primarily defined by the human presence on the Earth, and its impact on climatic, biological, and even geological systems. Our numbers have swelled from one billion in the year 1800 to six billion in the year 1999, and are expected to reach nine billion by 2050. Our agriculture, energy plants, cities, cars, airplanes, dams, fishing fleets, and many other technologies — combined with our enormous numbers — have changed the face of the planet. Our effect on Earth’s ecosystems is equivalent in scale to the coming of an ice age, or the impact of a large asteroid, and it is expected now that we will leave our imprint in the fossil record for eons to come. No matter how it all turns out for us in this and coming generations, geologists millions of years in the future (if there are geologists then) will be able to see our fingerprints on this period of history, etched into the layers of rock.

The question is, what will they see? A complete catastrophe, marked by an enormous die-off of species, the exhaustion of resources, and pollution so widespread and toxic that even human numbers dwindle rapidly? Or will they see a “near- miss,” a moment of danger, where global-scale catastrophe is contained just in time, and recovery and restoration begin in earnest — turning Earth’s future from “human wasteland” to “planetary garden”?

The answer to these question hinges on the answer to one more question: Will humanity manage to transform its economies, to convert them from destructive forces to sustainable and indeed restorative processes, in time?

Notice the word “economies”: while we often refer to a single “global economy,” the truth of the matter is that human civilization is comprised of a complex network of many different economic systems. Some of them are still free-standing, essentially subsistence economies, where people farm or hunt and live off what is around them, with relatively little interaction with global-scale processes. But even indigenous tribes living deep in the Amazon are increasingly tied into the world’s larger network of economic transactions, clustered (at least for reporting purposes) into nation states, and woven tightly together by trade, technology, and currency exchange. Still, as we begin this exploration of emerging alternatives to “economic growth” as we know it, it is important to bear in mind that “the global economy” is not a monolith. The process of using resources, creating value, and meeting human needs and aspirations looks very different from one place to another. Japan’s economy is very different from that of China, the United States, Brazil or Bhutan.

One thing that all of the world’s larger economic systems have in common is an absolute dependence on growth.We will explore the concept of growth in a more nuanced way later, but for now, we can simply acknowledge that the economic success of essentially every country in the world is measured by how quickly that country’s consumption of resources, production of goods and services, and resulting money flow is expanding. Fast growth is better than slow growth; no growth is bad; and “negative growth” (also known as “recession,” or shrinkage) is considered seriously catastrophic if it continues for more than a few months.

But if growth, in national economic terms, is always the goal, and if more growth is better than less growth, what does the future hold in store? It is very difficult to deny that we live on a planet of limited size and capacity. The Earth once seemed boundless to us; now, we jet from one side to the other in half a day. Researchers debate how many decades (not how many centuries) of oil are left to fuel the jets. Supplies of metals, fish, even fresh water are running low. And most worryingly, the waste and garbage from our activities continue to build up, sometimes in disturbingly visible ways (such as the enormous gyre of plastic waste in the middle of the Pacific Ocean), and sometimes in ways that are all the more dangerous for being invisible (such as the buildup of greenhouse gases in our delicately balanced atmosphere).

Under such conditions, to believe that growth as usual can continue indefinitely is not just ridiculous; it is delusory. Economies do get more efficient over time, and innovation does provide substitutes for some resources when they run out or get expensively scarce. But at some point, there is nothing left to substitute, no more efficiencies to capture, and too few resources to meet the needs. If growth has not stopped well before that point, and if our economies have not changed and matured into systems that do not require continuous physical expansion in consumption and production of finite materials and non-renewable energy, then a collapse is inevitable.

To achieve a sustainable, collapse-free future, it is not sufficient to talk about changing “the global economy”; we must change many different economies, all around the globe. For this reason, it is encouraging to see how many alternatives to the growth paradigm have emerged around the world in recent years. This diversity runs counter to the myth that only growth is good, much less that growth can continue forever. Countries like Bhutan talk consistently about “Gross National Happiness” (a phrase that has echoed around the world) and even measure happiness in sophisticated ways, while researchers in Austria — to pick just one example — have recently measured the “subjective well-being,” “quality of life,” and “time- prosperity” of that country’s population.2 Phrases like “Genuine Progress,” “Sustainable Society,” and even “De-Growth” appear more and more often in serious discussions of policy.

The change in the level of mainstream acceptance around these terms has come with astonishing speed.Prior to the year 2010,the idea that a concept like “happiness” would start competing with “growth” as a principal goal of national economic policy would have been laughable. It certainly remains controversial. But it is no longer marginal. A growing number of senior political, business, and institutional leaders have now acknowledged that economic growth, as we currently define it and measure it, is not the only important measure of human welfare. Pronouncements on this topic by people such as the UK Prime Minister David Cameron, French president Nicholas Sarkozy, and the leadership of China’s Communist Party have all generated global headlines in the last year alone. And in early 2012, the UN’s High-Level Panel on Global Sustainability — chaired by Presidents Zuma of South Africa and Halonen of Finland — noted the need for “The international community [to] measure development beyond gross domestic product (GDP) and develop a new sustainable development index or set of indicators.”

To understand where this sudden, contemporary surge in alternatives to growth is coming from, it is important to understand something about how growth became such a dominant paradigm in the first place. This report summarizes some of the key factors that have supported the dominance of “growth” in global history, while also providing a briefing on some of the contemporary political factors and technical initiatives that have led to this moment of sea change in public thinking on growth, happiness, and human well-being.

“Life Beyond Growth” also provides summary information on specific alternative indicators and policy initiatives — some of them many years in development — that have recently become more visible. Whether or not these alternatives will spread more broadly and take root more deeply is difficult to predict; probably most of them will not. In this respect, the report provides a “snapshot” of a global intellectual and political movement, one that is gathering steam, but being expressed in different ways in different parts of the world. It is difficult to summarize this movement in a conclusive way, because it is so diverse and changing so rapidly, almost from week to week. “Life Beyond Growth 2013” is likely to present a very different picture of this complex present reality.

In the end, regardless of which ideas and frameworks win out, we must find our way to a future where everyone, in every country, has the opportunity to experience quality of life, happiness, and well-being while living within the boundaries of what our planet can physically sustain. This is the central motivation behind this annual report on “Life Beyond Growth.”

The Rise of a Movement

Why did the interest among governments and public thought-leaders in these previously marginal questions about growth and happiness arise in the first place?

There appear to be at least three principal reasons: one is political in nature, one is more scientific and empirical in its origins, and the third is ethical.

Politically, the leaders who have recently spoken out in favor of new measures of happiness have done so in the context of reduced expectations for traditional economic growth, as measured by the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Prime Minister David Cameron of the UK, President Nicolas Sarkozy of France, and the Chinese Communist Party have in common that they preside over countries whose economies — for differing reasons — cannot provide previously promised and expected levels of growth in GDP terms. As the Secretary-General of the OECD, Angel Gurría, said in a very recent speech on this topic, “growth ‘as usual’ is not an option.”3 Measures of happiness and well-being provide these leaders with a viable alternative for demonstrating their success as leaders in providing for the welfare of their citizens.

These political calculations also have a basis, however, in emerging empirical analyses of the economic, social, and ecological realities of the 21st Century. Leaders of all kinds increasingly understand the complex challenges we face as a world, in areas ranging from global climate change, to environmental decline, to local conflicts over increasingly scarce resources. Faced with an ever- growing mountain of relevant scientific facts and trends, many leaders are realizing that “Growth as Usual” — a term we will adopt throughout this report — is no longer viable as a long-term, overarching societal objective. Their interest in finding alternatives has been matched by an upsurge in robust, scientifically based approaches to defining and measuring alternatives that previously seemed too vague or too difficult.

And finally, growth — as an over-arching paradigm and ultimate social goal — has been the subject of continuous critique by ethically-minded thinkers for decades. Their championing of other values, such as equity, altruism, and a less materialistic way of life, has always found adherents at the margins of modern industrial societies. Now, it appears, their philosophical arguments have found common cause with the political needs of national leaders, as well as the empirical and analytical tools of contemporary research. In the rise of democracy- based protest movements now emerging around the world, they may also have found a new, popular voice.

But What is “Growth”?

“Growth” is, of course, a word with many possible interpretations. In the political and economic context of our time, and especially in the common language of political speeches and newspaper articles, the word “growth” is a blend of at least four different concepts:

- The expansion of humanity’s physical presence on the Earth (the size of our cities, farms, and industrial areas);

- Increased production and consumption of goods and services (the output of our factories and offices);

- Increased monetized activity in our economies (the flow of currency between buyers and sellers); and

- General technical and industrial progress (the increased sophistication of our technologies and their increased diffusion and adoption).

We will offer more precise definitions later, but even in the common, conflated, and somewhat confusing sense of the word as described above, people are increasingly realizing that that Planet Earth cannot sustain endless “growth” — at least, as we have been practicing it up to now.

The search for alternatives to Growth as Usual has led quickly to concepts of human happiness and well-being. Philosophically, the world appears to be on the verge of a collective “aha!” moment about the meaning of economic activity, perhaps even a collective realization about the meaning of life itself: that the purpose of all our striving is not to increase the quantity of stuff and money in our lives, but to improve our quality of life.

The most compelling and publicly visible evidence of this “collective aha” can be found in the recent actions and public pronouncements by the leadership of the three diverse nations noted earlier, China, the United Kingdom, and France. All three nations have moved seriously, and very publicly, to begin measuring the happiness and well-being of people, and they claim that they will reduce the dominance of economic growth goals in policy making. They are not the only nations doing so; but their actions have been particularly noteworthy for the amount of media attention they have received.

From Bhutan to Britain

The policies of these countries have been influenced, indirectly if not formally, by the pioneering work of the tiny mountain kingdom of Bhutan, whose notion of “Gross National Happiness” has long generated interest and headlines around the world. Bhutan’s efforts to measure human happiness and well-being as the principal scorecard for national success have also inspired or influenced similar headline-making initiatives at all levels, from towns and cities in the United States (such as Seattle), to state-level governments in India (such as Assam), to international collaborations like the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, better known as the OECD.

These top-down, governmental policy initiatives are mirrored by a growing number of bottom-up grassroots and intellectual movements, including the “happiness movement,” the “downshifting movement” (reflecting people who choose to work and earn less in exchange for more time and higher quality of life), and the “de-growth” movement (a largely academic discussion on how to restructure national economies in ways that are not dependent on growth).4However, this is not to say that the world is on the verge of turning its back on economic growth, or embracing a future of “simple living” and consumption reduction. Far from it: traditional economic growth remains essential to the achievement of the United Nations’ Millennium Development Goals; it continues to frame the national policies of nearly all nations; and even the “pioneer” nations mentioned above (including Bhutan) are also resolute in their efforts to maintain steadily increasing Gross Domestic Products.

What is different about this moment is not its revolutionary nature, but its evolutionary character. After thousands of years of steadily increasing growth, topped by an extraordinary “growth spurt” as a species in recent history, it seems possible that the human species is realizing that it will soon be “all grown up,” at least in physical terms. Like any human teenager, our physical growth as a species must soon come to a stop, to be replaced by a focus on the long-term development of our knowledge, skill, and wisdom.

In part, the purpose of this report is to tell the story of how the world arrived at this moment. In part, it provides a summation of the current “state of the art” when it comes to rethinking economic growth in favor of other goals and other scorecards. And in part, it attempts to provide some insights and guidance for those who are interested in helping this transition from an old worldview to another, broader, and more sustainable worldview to continue, and to accelerate.

“Growth” is a physical phenomenon, not an abstract concept. For centuries, growth has also been a fundamental, defining element of human civilization. The first meaning of “to grow” is “to become larger.” Humanity’s physical presence on planet Earth — how many of us there are, the resources we use, the kinds and quantities of things we create, the changes we make to the natural systems around us, the waste we produce — has been getting larger and larger, in every measurable way, since the first modern humans stepped out of Africa and began to spread themselves across the surface of planet Earth. Humans do many interesting things, but if viewed from somewhere out in space, over a long period of time, here is the first thing an observer would notice about us: we are growing.

In the past century or two, the speed of our growth has accelerated; since 1950, it has accelerated dramatically. The benefits to humans of this accelerated growth cannot be denied: in general, by expanding our numbers and our capacities, human beings are living longer lives, filled with more amazing and fulfilling opportunities, than anyone could have imagined just a century ago.

But today, the impact of both the speed and the scale of human growth — that is, the process of our presence on the Earth getting much bigger, much faster — is significantly disrupting the rest of life on this planet. Our growth has replaced vast areas of enormously complex natural ecosystems with the much simpler systems (in ecological and biological terms) of agriculture, industry, and urban living. Even the chemical balances of vast bio-geophysical systems — the atmosphere, the oceans, forests, soils — have been disrupted. The results of these replacements and disruptions are now keeping an expanding corps of researchers very busy trying to understand what is happening.An expanding global class of professional environment and sustainability policy-makers, planners, and managers is struggling to change those systems that appear to be causing the biggest problems.

And this is just the environmental or physical side of growth. On the social side, the world is currently witnessing what happens when rapidly growing populations expecting rapidly growing opportunities begin to rebel against political and economic systems that are not delivering those opportunities. The Arab world’s current transformation was partly triggered by problems such as rising food prices, water scarcity, and a lack of jobs for educated young people — all byproducts of extremely rapid growth, especially in population. The final result of the Arab world’s transformation is impossible to predict; but the world will certainly never be the same.

So the question of whether growth is happening is not in dispute. The question of whether growth is always good — whether growth should continue to be the unquestioned, fundamental goal of human economies and societies — is another matter. Questions like “What should keep growing? What should stop growing? And what should shrink?” have become some of the most important questions of our age, posed by Nobel Prize-winning economists, heads of state, and increasing numbers of ordinary people.

Most importantly, can growth continue? Have we begun to reach the “limits to growth” — ecological and social — that we were warned about decades ago? And if so, how can we re-organize our economies so that they can produce happiness, well-being, and expanding opportunities for all, without having to “gnaw this planet to the bone”?

Growth, Economic Growth, and Monetized Economic Growth

At this point, it becomes important to introduce a few important definitions and distinctions.

Growth is physical growth, as described above.

Economic growth is a related concept, but it is not the same thing as simple “growth”. Paul Romer, an economist at Stanford University, defines it this way: “Economic growth occurs whenever people take resources and rearrange them in ways that are more valuable.” He makes the analogy to cooking: raw ingredients go into the kitchen. Labor, knowledge, energy and technology are applied. Beautiful meals come out. The beautiful meal is far more valuable than the raw ingredients, thus creating an increase in value: economic growth.5

But how do we measure value? In the modern world, we measure it with money. The beautiful meal is worth whatever someone is willing to pay for it. This way of measuring value creates some difficulties in measurement. If the beautiful meal is prepared by your mother, it may have great value to you. But that value will not be recorded in the economic statistics of the nation, because you will probably not pay money to your mother. Theoretically, her act of cooking and serving you a delicious meal will contribute to the economic growth of your nation; but because it is not paid for, and because no monetary transaction is reported to any official agency, the meal will remain economically invisible.

Imagine, however, that your mother presents you with a bill for the meal. You pay the bill in cash. She records the income, and duly reports this transaction to the authorities (e.g., as part of her tax declaration). Then, and only then, will you and she have contributed to your nation’s measured economic growth — she by producing the meal, and you by consuming it and paying for it.

In simple terms, our modern world is obsessed with increasing its measured, or “monetized,” economic growth as described above. The measure invented to summarize the state of monetized economic growth at the level of countries is the Gross Domestic Product, or GDP. This number, which is the most-reported measure of progress and success for the world’s nations, does an effective job of reflecting the level of monetized economic activity. However, its flaws are many. Among them is the perverse fact that disasters, accidents, and acts of war tend to make the GDP go up, as nations mobilize their economies to recover, make repairs, or go on the attack. Moreover, many sorts of costs, ranging from environmental degradation to deep social inequities, more often result in additions to the GDP than they do reductions.

Growth as Usual, as used in this report (and as used by commentators such as the head of the OECD cited in the Introduction), refers to this amalgamation of physical expansion with monetized economic growth, leaving aside qualitative, good-or-bad distinctions among kinds of growth, and without any consideration to the systemic limits to growth. “Growth as Usual” is so well epitomized by the indicator we call the “GDP” that these two terms are very nearly synonymous. The GDP measures Growth as Usual.

The many critics of the GDP over the years have included the indicator’s inventor, Simon Kuznets; even he warned against using it as a measure of overall welfare.6 All these critiques have mostly fallen on deaf ears in national policy circles — until now. In the past few years, criticism of using the GDP as an ultimate measure of national progress has reached the highest levels of several national governments. In March 2011 even the Chinese government, for whom rapid economic expansion has been top priority for decades, made pointed public statements about its intention to reduce the emphasis on pursuing GDP-measured growth, in favor of emphasizing human happiness and better care for nature.

It is no exaggeration to say that a global shift in economic thought, and even national economic policy, appears to be under way.The extent of this shift is still to be determined,but it has many strands, incorporating advances in psychology and brain science, concerns about climate change, changing demographic patterns, and more. This report summarizes many of those strands and provides a window into the philosophical, psychological, and technical aspects of a very disparate global movement whose common message, if it had one, might be summarized this way: “We do not have to continue pursuing Growth as Usual, nor can we. But there are other things we can do. There is life beyond growth.”

But what is it that lies “beyond growth”?

An Economy of Happiness

The word that now most often appears in place of “growth” as a goal for the world’s economic systems is “happiness.” There are other words and phrases that follow along in its wake, including “flourishing,” “well-being,” “prosperity (without growth)”, and even “de-growth”. But when leading nations like China or the United Kingdom do speak out on this issue, and begin the process of crafting alternative measurements of overall success, “happiness” is the word that leads the news.

The rise of “happiness” as the leading candidate for a revised set of national goals can partly be traced to the tiny Himalayan nation of Bhutan, which lies between China and India. The King of Bhutan has long been a very public promoter of a new concept and measurement process called “Gross Domestic Happiness,” as a counter to the GDP. The “GDH” (or sometimes “GNH” — Gross National Happiness) is now actively measured in Bhutan, by survey. Through the diffusion power of international meetings, traditional media, and new social media, the idea has spread around the world.

As the concept has gained some distance from Bhutan, it has appeared increasingly mainstream and acceptable to the industrial powers.The British news magazine The Economist recently described it this way:

“Academics interested in measures of GDH (gross domestic happiness) were once forced to turn to the esoteric example of Bhutan. Now Britain’s Conservati- ve-led government is compiling a national happiness index, and Nicolas Sarkozy, France’s president, wants to replace the traditional GDP count with a measure that takes in subjective happiness levels and environmental sustainability.” (12 May 2011)7

This is not to say that Bhutan, or any other nation, has given up on the idea of growth in monetized economic terms; indeed, Bhutan itself has experienced rising GDP at a brisk clip in recent years — just under seven percent — driven by its sales of hydroelectricity to a fast-growing India, and by tourism. (Ironically, some of the tourists in Bhutan are people who want to visit the birthplace of Gross National Happiness.)

Moreover, the same nations now speaking about happiness and well-being as alternative goals are also still quite politically committed to Growth as Usual. Consider China: at the 2011 “BRICS” economic summit, the governments of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa (the “BRICS” countries) released a joint statement, the “Sanya Declaration,” which opened with commitments “to assure that the BRICS countries continue to enjoy strong and sustained economic growth,” which is universally seen as the only path out of poverty.8

Of course, poverty alleviation is not a driving concern for the economic growth policies of the world’s most industrialized and wealthiest nations. But can nations that are already wealthy create and sustain “economies of happiness” without economic growth? This is the question that is now seriously being explored by a growing corps of economists and policy makers around the world.

Happiness, Money, and Economic Growth

It is said that money, the measuring stick for economic growth, cannot buy happiness. But many studies reveal that, in fact, money can buy happiness — up to a point. Measurements of people’s happiness and general satisfaction with life tend to rise as their monetary incomes rise, across all cultures, until those incomes reach a certain level. After that certain level of income is reached — and it has been variously calculated as somewhere between USD 15,000 and 75,000 per person, depending on what country you live in, and on how you frame the research — happiness ceases to rise.

In simple terms, the growth of your nation’s GDP will lift your nation up to a strong and stable level of happiness, up to somewhere around USD 15,000 per person. After that, GDP growth is buying many things; but additional happiness is probably not among them. This is often called “Easterlin’s Paradox,” after economist Richard Easterlin, who first studied the phenomenon in detail in the late 1970s.9 The “paradox” is that we continue to pursue monetized economic growth in the belief that it increases happiness, when research shows that it does not. Easterlin’s early work has since been extended by many other researchers, including (most prominently) Bruno Frey, Richard Layard, Daniel Kahneman, and Ruut Veenhoven.10 Researchers tend to disagree on the question of whether the increase in happiness stops after reaching the USD 15,000 level (Easterlin’s view), or whether it simply slows down a lot (as Kahneman’s and Veenhoven’s work seems to show).11

One can conclude that growing the level of monetized economic activity is not unimportant in efforts to improve human welfare. Indeed, it remains essential; but only, says the research, in those cases where nations are experiencing incomes significantly below USD 15,000 per person (in GDP terms). After that, it is unclear exactly what purpose — in terms of improving human happiness and satisfaction with life — economic growth serves.

Because economic growth, as currently practiced, is coming at such a great cost to the Earth (and often to human health as well) without returning any measurable increase in human happiness, the question of growth and happiness has become one of the most essential issues of our times. What is an “economy of happiness”? How do we achieve it? Is it the same as a “zero growth” or “steady state” economy? Or does it depend on new forms of “green growth”? Is there room for “de-growth” without inadvertently triggering some dramatic reduction in happiness?

These are not easy questions, but in these early decades of the 21st Century, the world appears to be grappling with them, more and more seriously. We now turn to the essential history behind these questions as well as the ideas, measurements, and analyses that frame much of the current debate about the relationship between growth and happiness.

Chapter 2: The Rise (and Possible Future Fall) of the Growth Paradigm

The Origins of Economic Growth

Population growth is just one factor, one “ingredient,” in the recipe we call economic growth; but it is obviously a fundamental factor. It is also, very likely, the oldest factor: successful biological adaptations by the human species allowed us to multiply and spread out across the Earth, into many different ecological niches. Very soon, however — so soon as to almost be called “simultaneously” — we humans also began to develop tools and technology (such as weapons and methods of housing construction), as well as cultural innovations (such as advances in language and cultures of farming) that worked together, systemically, to improve the survival rates of our relatively helpless babies, and to increase those babies’ chances of living long enough to reproduce.

Pushing “Fast Forward” on the timeline of human history, and viewing that timeline from an imagined perspective outside our planet’s atmosphere, produces an extraordinary “growing and spreading” effect. People move into every inhabitable corner of the planet, and even into some uninhabitable ones. Forests and swamps turn into farmland. Cities grow like mushrooms. Bases with small human populations eventually appear even at the frozen poles, and in space stations orbiting the planet. The number of people accelerates steadily, together with an increase in the natural resources they consume, the machines they make, the pleasures they enjoy, the inventions they come upon … and the destruction they sometimes inflict on one another.

Dipping periodically into this fast-forward view of history, we would at various times see the important advances in the mechanisms that support the ever-increasing and ever-more-productive use of resources to increase and improve the material standard of living for human beings.We would see Roman roads and aqueducts, the development of Chinese and Mongolian systems of bureaucratic organization and trade management, the invention of banking in Renaissance Italy, the rise of science, the spread of technology, and so much more.

We would especially notice the rise of energy consumption, as humans learned new ways to convert substances found in the Earth’s crust into heat and electricity. We would witness the spread of information and communications technologies, the densification of trade networks, and — assuming we knew where to look — a truly phenomenal increase in the production and flow of money around our planet. All of these phenomena have contributed to the exponential expansion of humanity’s numbers, which in turn increase the amount of human activity driving all those phenomena, in a self-reinforcing spiral of transformative change.

But when did growth really take off? And why?

1849-1972: Growth’s Explosive, Bloody Century

The modern “growth of growth” is a story that has no exact beginning. There are many decisive turning points in the story, such as the European discovery and colonization of North and South America, or the end of European feudalism and the establishment of commerce-and-trade-based governments, which freed up the entrepreneurial skills of entire classes of people and accelerated the spread of new technologies. These historical shifts can be seen as contributing to the “cause” of growth, but they can also be seen as an “effect” of growth, as swelling populations spread out, searching for — and demanding — more freedom and better technologies to improve their lives.

But at some point, growth did “take off.” If one looks at graphs of data showing the increase in population, resource use, production, GDP, trade, travel, waste, communications density, and many other telltale indicators of economic growth over the past couple of centuries, a pattern is easy to see. First, around the middle of the 1800s, the graphs (which up to then appear nearly flat) tip up, like an airplane taking off from a runway. Then, around 1950, they all tip up again, achieving the steep, nearly vertical trajectory of a rocket. Most such graphs of global change continue to have that shape today, and a group of scientists studying these trends have given a name to this phenomenon: the “Great Acceleration.”

Figure 1: The “Great Acceleration,” reflected in 24 global growth trends from 1750 to 2000, assembled by the International Geosphere- Biosphere Program (Steffen et al.)12

To help us understand this phenomenon, it can be useful to connect these “take-off points” in the global system to real events in history. As our first turning point, and as the symbolic “starting gun” for the acceleration of economic growth in a modern sense, consider the California gold rush of 1849.

Digging Up Money

The California gold rush is symbolically important to the history of growth, because it came at the end of European-American expansion across

North American continent, which many historians have recognized as the moment when the “frontier closed” — mostly for the United States, but also, in some ways, for the European colonization movement generally. After that, there were few parts of the planet (with reasonably mild climates) left for humans of any origin to migrate to. Nearly all the best habitats were already well inhabited by other humans.

The American Gold Rush was also important because it marked one of the last historical moments when people were able to migrate to a place where they could literally “dig up money.” Gold has long been the preferred currency of many economic systems, from ancient times to the present, regardless of whether other currency systems were also in place. Other resources, ranging from oil to trees to fish, have to be sold — that is, converted into whatever form of money is in use by that society, if the harvester of those resources is going to be able to profit from them economically. Barter on a vast scale is too complicated, so converting “stuff ” into “money,” through the medium of a monetized economic system, is a necessity.

This conversion step of being “sold” is also possible for gold, of course; but it has often been practically unnecessary. In many situations, gold is money.This can still be seen today, in many ways. Here are three examples:

- In countries like India, people still often avoid banks and “wear their money on their body” in the form of gold bracelets, necklaces, and other jewelry. Efforts to convince people to sell their gold and turn it into monetized bank accounts meet stiff resistance, especially among the poor.

- In some countries, governments still actively seek out gold deposits to develop with the express purpose of “putting the gold in the bank” and improving that nation’s balance sheet. A controversial gold-mining operation being developed in Rumania, for example (Rosia Montana), has been described by a former senior official familiar with the project as having, in part, that purpose.13

- In the world’s financial markets, gold is still treated somewhat specially (compared to other metals and commodities). When stock and bond markets have trouble, for example, people look to gold as a more stable “store of value,” which is one of the classic definitions of money.

However, while the use of gold as “money” persists, the California Gold Rush can be said to mark (very roughly) the end of an historical period of imperial expansion driven by gold, as well by the economically dominant European powers of the day. Starting with Columbus’s famed journey to the “Indies”, these powers had been in a constant search for lands to acquire with resources to exploit — and gold was always the greatest attractor. Most of the early European explorers were “driven by an insane lust for gold,” notes the editor of The Great Explorers.14

By the late-1800s, when essentially all lands were spoken for by some country, and all the sources of gold (and many other resources) had been divided up among nation states, attention turned in earnest to the process of converting resources to monetized economic activity.

Another way of saying this is that the focus of human activity changed from pure “growth” (as humanity spread out on the planet) to “economic growth” — that is, from amassing raw resources such as land and gold, to the process of converting the available resources into other things that had perceived value, and that could be converted into money.

Growth’s “Secret Ingredient”: Energy

The process of combining raw materials with labor and technology to produce money was greatly accelerated by the energy and technology revolution (the “industrial revolution”) that began to take form in the late 1800s. To return to Paul Romer’s “economic growth is like cooking” analogy, it was as though all of humanity had been struggling, for all of history, to cook over small wood fires with primitive utensils. Then suddenly, toward the end of the 1800s, humanity was given a fully equipped modern kitchen — with a gas stove.

Adding oil, gas, and coal to the recipe as plentiful energy sources, together with the development of coal-fueled electricity production, created a powerful upgrade in the capacities of the world’s economies to create additional value that could be monetized. Trees could be cut faster to generate paper that became newspapers, sold to a growing population of increasingly better-educated readers. Cotton could be ginned and woven at high speed to become fabric and garments for the world’s ever more fashion conscious shoppers. Around the turn of the new century, 1900, cars and other industrial products were rolling off fast-growing production lines that were driven by these extremely powerful new forms of energy. The industrial production process became increasingly efficient at turning ores into metals, for example, and then turning those metals into shapes and forms and machines that could, in turn, use that same energy to do increasing amounts of work, for which people were prepared to pay increasing amounts of money. The cash registers of the world were suddenly ringing at breakneck pace.

To get that money, more and more people in these growing centers of industrial activity went to work, essentially selling their time so that they could buy the products that they, and other people like them in other factories, were making. The links in this chain of production and consumption were often explicitly designed: Henry Ford, for example, structured his enterprise in such a way that workers at his car factories made just enough money to afford a car, so long as they continued working (to pay back the inevitable loans).

But there were many problems and conflicts in this process,as any quick reading of history reveals,from the labor struggles that resulted in unionization, to the terrible and grotesque shortcuts taken in the industrialized food systems (as documented by, among others, the American writer Upton Sinclair in his novel The Jungle in 1906), to the trade, power, and political disputes that resulted in the first true World War.

War exacted a horrific cost in both human and environmental terms. Unfortunately, war proved to be a rather more positive undertaking from the perspective of economic growth.

The Wars for Growth

While there are many ways to interpret the causes and driving factors in both World War I and World War II, these global-scale mega-disasters of the 20th Century were at least partly driven by the unquenchable thirst of that era’s ambitious empires and nation-states for rapid economic growth, and for the key factors that make growth possible: energy, land, raw materials, technology, trade and investment systems, all managed by well-trained, disciplined, hard-working people.

While World War I is mostly remembered for having been “caused” by the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand in Sarajevo, many of the underlying dynamics that were triggered by that fuse had to do with the control of resources and trade routes by nations that had empires to protect (or that had imperial ambitions). Indeed, empire- building has, since the dawn of recorded human history, always been driven by political visions of continuous and rapid economic expansion. The World Wars of the 20th Century equipped these ancient habits with modern technologies, which amplified the destructive power of the empire-builders by many orders of magnitude. Those technologies are dependent on access to vast amounts of energy, leading some modern commentators to interpret some of the main battle action of World War II — such as Japan’s Southeast Asia expansions, Germany’s forays into Russia, and the US entry into both the Atlantic and Pacific theaters — in terms of the need to control key resources such as oil. (See for example Daniel Yergin, The Prize, 1990.15)

Many historians note that the deep economic depression experienced by the industrialized world during the 1930s was only finally ended by the conversion of the industrialized nations to a war economy. When at war, massive amounts of state investment are poured into massive amounts of technology development and industrial production, and everyone is put to work. Some note that the world’s industrial economies have essentially continued to operate in a wartime mode, right up through the present day, driven first by the “Cold War,” and more recently by the “War on Terror.”

As noted earlier, war has proven to be one of the world’s most reliable ways for causing its measurable, monetized economic growth — its “Gross Domestic Product” — to appear to rise. Indeed, the GDP itself was itself used as a kind of weapon of war.

The Rise of the GDP

The Gross Domestic Product is, in simple terms, a measure of all the monetized economic activity that takes place in a country, during a specified period of time. When the numbers associated with the GDP are generally going up, this is called “economic growth.” When the numbers are going down, this is called “recession.” And when recessions continue for a longer period of time, they are usually called a “depression.” For all practical purposes, and for most of the last century, the GDP has been reported to the global public as though it were identical to economic growth, and therefore identical to progress overall, in every nation.

This formal way of measuring monetized economic activity was born in the middle of the explosive century that we have called “the growth of growth”. The GDP was initially created by American economists to help the US government try to cope with the economic depression of the 1930s. However, it proved even more valuable in planning for war-time economic production. The GDP allowed the government to find factories that were not fully utilized, and ensure that production was maximized. According to economic historians, Hitler had no GDP (or similar set of effective national economic statistics), and as a result many German factories were producing much less than they could have. This led to a big, and probably decisive, difference between the two warring factions in terms of numbers of tanks, planes, bombs, etc. that they could throw at each other (see Cobb et al.,“If the GDP is Up,Why is America Down?”, Atlantic Monthly, 1995).16

But the inventor of the GDP, Simon Kuznets, became increasingly worried that his invention would be misused. He testified on this point before the US Congress as early as 1934, warning that the new national economic statistics should not be used to assess the overall welfare of the nation. And in the 1960s, he wrote that “Distinctions must be kept in mind between quantity and quality of growth, between its costs and return, and between the short and the long run … Goals for ‘more’ growth should specify more growth of what and for what.”17

The warnings of the GDP’s inventor were, however, completely ignored, and as the world’s financial and economic systems grew, the GDP became more and more central as a scorecard of success for those systems. International financial agreements, political campaigns focused on growth, United Nations indicators reflecting the socio- economic status of countries, regular reports on GDP-measured Growth as Usual in nearly every country’s news media, and many other examples of continuous and repeated use served to inscribe the GDP (and other measures of economic growth) deeper and deeper into the mindset of decision- makers, nearly everywhere on planet Earth.

When one uses only the measure of the GDP as a scorecard, human civilization appears to be winning the Game of Life by a landslide. It is only when one begins looking at other measures that we realize that economic growth has also been creating growing amounts of trouble.

The Tipping Point for Growth as Usual

Starting in the 1950s, the growth curves for many indicators of human expansion – not just monetized expansion as measured by the GDP, but physical expansion, measured in terms of numbers of people and the amount of resources they use and discard – tipped up dramatically, as noted earlier. It is as though the new age of rockets and space exploration was serving as a mirror for the rocketing trends here on Planet Earth.

The reasons for this “tipping point” are many, but surely the combination of war and peace – that is, the Cold War between the capitalist West and the communist East, which never flared up into global-scale armed conflict — was a major cause. These competing world economic and political systems, led by the United States and the now- defunct Soviet Union, made vast investments in science, engineering, and industry, as well as in the education needed to fuel technological advance. Western countries also promoted an increasingly consumerist lifestyle, partly as proof that the Western model was preferable to the state- controlled forcible “equality” of the Soviet bloc nations.

The result was spectacular growth, in every nuance of the term described earlier: more people, more production and consumption, more money moving through economies, and accelerated technological development. That growth was also, essentially, unquestioned. With the exception of the early warnings from researchers and writers — most visibly from US authors such as Rachel Carson (Silent Spring, 1962) and Paul Ehrlich (The Population Bomb, 1968) — the idea that there might be planetary limits to human expansion was almost unheard of.

1972: The Launch of the Global Growth Debate

In this historical review, the year 1972 emerges as a key milestone year. This was the year when the very last US Apollo spaceship took off, and the US program of moon exploration was laid to rest because of pressing national budget problems. Interpreting it symbolically, one might see in this turning point a tacit admission that we are bound to our home planet. We cannot escape its boundaries and find new planets (or moons) to inhabit anytime soon.

More concretely, the year 1972 also marked the launch of the United Nations’ first global environmental conference (in Stockholm), which reflected many newly emerging worries about the future of the planet. The “Stockholm Conference” is now seen as the kickoff for what became a series of global summits on environment and development issues over the ensuing decades.The year 1972 also marks the creation of the world’s first environment ministries and the passage of the first comprehensive environmental laws, in the United States and in several European countries.

But no other event captures the importance of 1972 as a turning point in the history of growth as the famous Club of Rome/MIT study, The Limits to Growth. This groundbreaking book reported on a study that used a computer model of world population growth, industrial production, resource use, and pollution. Its young authors (average age about 30) warned of serious resource and environmental trouble ahead if human expansion continued on its then-current course. The book burst onto the world stage like … well, like a rocket. It sold millions of copies, generated hundreds of newspaper and magazine headlines, and it launched an acrimonious global debate on the long-term prospects for economic growth. That debate continues to this day.

During the decade of the 1970s, other books and public voices questioning the standard model of economic growth also began to emerge. These voices not only questioned the dominance of the “growth paradigm” (as some people began to call it), but also offered alternative visions of what a national or global economy could look like if it was not focused solely on generating unending growth.

Some of these voices, such as the German-British economist E.F.“Fritz” Schumacher in his bestselling book Small is Beautiful (1973), helped to fuel the counter-cultural movements of the late 1960s and 1970s. Others launched small-but-stubborn counter-movements in the academic discipline of economics itself, such as the classic work of Herman Daly on Steady State Economics (1977).

These cultural and intellectual movements were, however, quite marginal. They had vanishingly little impact on growth itself, or on the continuing development of the institutions, policies, and news reports that were anchoring the GDP ever deeper into the prevailing mindset. Despite the big splash made by The Limits to Growth, its actual reception in the political and academic circles of the day was hostile in the extreme. For decades, the book was regularly held up (and often ridiculed) as an example of wrong thinking.

However, the history of the debate on growth during the period from 1972 to today could also be graphed as a gently rising line — one that starts to look more and more like a rocket. Public concerns about climate change, biodiversity loss, large-scale poverty, and other problems have grown rapidly in the last decade. A wide variety of scientific studies have established quite conclusively that human expansion and the ecological systems of the planet are on a collision course; indeed, the collision was probably already under way. Perhaps the most poignant indicator of this mega-shift in global opinion about the actual limits to growth was the publication, in May 2008, of a front-page article in the Wall Street Journal, acknowledging – for the first time – that the arguments in 1972’s The Limits to Growth were essentially correct. (That newspaper’s contributors and editors had long been among the strongest critics of the original arguments in that book.)18

Today, it would be a gross exaggeration to say that either the expansion of humanity’s presence on the Earth, or the primacy of economic growth as the top-priority policy goal of nearly all national governments, are under serious question. But there are genuine signs that history is approaching one of those turning points which will be marked by historians as a “before and after” moment. There are increasing indications, particularly in the form of statements and actions by political leaders, that we are approaching the moment when “life beyond growth” is becoming possible to imagine. The previously unassailable fortress protecting economic growth — a fortress whose building blocks include global financial systems, national statistics, enabling institutions, and the core beliefs of both leading economists and global political leaders — is starting to crumble.

But before examining those signs, let us look first at the elements of that fortress in more detail.

Chapter 3: The Building Blocks of the Growth Paradigm

For the past century, “economic growth” has been more than a social and economic goal: it has been a dominant paradigm, a way of thinking about the purpose and structure of human civilization.

A “paradigm” is a philosophical or theoretical framework. It is a set of ideas and concepts that, in turn, can serve as the foundation for laws, rules, customs, beliefs, and ways of life. In professional disciplines, paradigms are the fundamental concepts that determine how that discipline is practiced. The history of science, for example, is a history of paradigms establishing themselves (e.g. Newton’s laws) and then getting replaced or extended by new paradigms (Einstein’s theories).

When a paradigm is operating at the level of a whole society and its economic systems, that paradigm can become the basis for everything from how trade and commerce is organized to how individuals make personal decisions about their lives. As the previous section described, economic growth emerged during the last century as a globally dominant paradigm, affecting the laws, structures, customs, values, and habits of the societies containing the vast majority of human beings. It is important to note that the paradigm, as a mental construct, was mostly based in the lived experience of human beings, as technologies improved, life-spans lengthened, energy became cheap and easy to obtain, and opportunities expanded. But the paradigm was also supported in intellectual, legal, and cultural ways.

Wherever one looks today — from the economics textbooks to the bank accounts of individuals, from political discourse and international negotiation to the chatter between neighbors — the “philosophical and theoretical framework” of economic growth is always present. This chapter describes some of the elements of this globalized paradigm, which serves as a reinforcing foundation to the continuous physical processes of resource extraction (and exhaustion), distribution (usually unequal), over consumption (or under consumption), pollution, and waste that are among the most problematic signature elements of economic growth.

Foundations in Economic History

In the 1700s, British social philosopher Jeremy Bentham introduced a new concept to describe the sum total of humanity’s happiness. He called this concept “utility,” and “maximizing utility” became a central focus of the emerging discipline of economics. However, measuring utility proved to be exceedingly difficult, and in the early 20th century, economists resolutely shifted their attention away from “happiness,” which could not be observed, and onto observable phenomena.This shift was partly driven by the desire to make the social science of economics more like the “hard” sciences, such as physics or chemistry, disciplines in which only that which can be observed is acknowledged to be “real”.

In 1920, Alfred Marshall (UK) noted that “desire,” a key element of utility, could only really be observed in the price someone was willing to pay for a product or service. In 1932, Lionel Robbins (UK) argued strongly that economics should not be concerned with the highly subjective concept of “happiness,” but with economic behavior, as reflected by purchase prices and purchasing decisions. Paul Samuelson (US) called this “revealed preference.” Ideas like these established a paradigm for economics that entirely dominated the 20th Century: utility, the sum total of human happiness, was effectively made equal to money.

In ways both subtle and explicit, this shift in economic theory implied that the more money people had, the happier they would be; and this in turn created the intellectual foundation for a century of preoccupation with economic growth as measured by the GDP.

The Prominence of Economics and Economists

Another important pillar holding up the growth paradigm is the high relative status afforded to economists. Economists are prominent in all modern industrial societies. They play a highly public role as opinion leaders, policy-shapers, political advisers, and media commentators. Because mainstream economics is focused so intensely on monetized economic activity — how to “stimulate the economy,” “increase employment,” “avoid recession,” etc. — the vast majority of economic language in the public sphere is focused on maximizing growth.

Perhaps the most compelling indicator of the historical dominance of the growth paradigm in economic thinking — and also an indicator of the cracks in that paradigm — is to be found in the so-called “Nobel Prize in Economics.” This highly publicized annual award is not actually a “Nobel Prize” in the formal sense,meaning one of the prizes awarded by the Nobel Foundation and initiated by Swedish inventor Alfred Nobel at the signing of his will in 1895.The economics prize was added much later, in 1968, and was established independently by the Bank of Sweden.The formal title is “Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel.”

With relatively few exceptions, the “Nobel Laureates” in economics have all been rewarded for their contribution to the enormous body of sophisticated theory and analysis tools that supports, as its main purpose, the growth of the economy. To cite just a few typical examples, one can look at the Bank of Sweden’s summary explanations for why the Prize was awarded:

- “for his analysis of monetary and fiscal policy under different exchange rate regimes and his analysis of optimum currency areas” (Robert Mundell, 2000)

- “for a new method to determine the value of derivatives” (Robert C. Merton and Myron S. Scholes, 1997)

- “for his contributions to the theory of economic growth” (Robert Solow, 1987)

- “for their empirical research on cause and effect in the macroeconomy [related to forces affecting the GDP]” (Thomas J. Sargent and Christopher A. Sims, 2011)

In recent years, however, the prize has occasionally been awarded to people whose work, while not exactly in conflict with traditional growth- centered economics, at least symbolizes an expansion of the discipline’s mainstream to include factors other than the behavior of firms, the movement of money, and the dynamics of markets. Of special note are Amartya Sen, cited for “for his contributions to welfare economics” (1999), and Elinor Ostrom, “for her analysis of economic governance, especially the commons” (2009). Sen is known for championing the well-being of the poor, while Ostrom is known for work on resource and environmental management.

As a final indicator of the prominence of economists in the global dialogue, a search on the word “economist” in the current news articles that are indexed by Internet search giant Google produces about 30,000 results (as of 28 September 2011). This is greater than the results for “singer,” (29,000), “athlete” (27,000), “journalist” (25,000), “businessman” (22,000), “politician” (19,000), “scientist” (19,000), “musician” (16,000), or, of course, “environmentalist” (5,000). Scoring slightly higher were news article citations involving the word “lawyer” (36,000) and “doctor” (39,000).

Economists are truly among the elite when it comes to professions having influence over our daily interpretation of reality; and when interpreting reality, they tend strongly to focus on growth and related issues.19

The Development and Use of Economic Indicators

The previous section described the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and its extraordinary role as perhaps the world’s most important and widely accepted indicator. But the GDP is hardly alone as a statistical pillar holding up the paradigm of economic growth as the overriding concern of human striving.

Nations, together with the supranational structure of agreements and institutions that guide global financial affairs, use a very wide variety of measurements to reflect different facets of the world’s pursuit of economic growth.These include, to cite just a few examples, the unemployment rate, the rate of inflation, the relative values of currencies, the prices of many key commodities, the combined value of shares sold in the world’s stock markets (stock market indices), the price of housing, the level of household debt.

The combined impact of these economic indicators, which are reported with great frequency and priority in the news media of most nations, is enormous. They frame a great deal of civic discourse at all levels, from their dominant role in national political debates to their frequent reference in family conversation in the kitchen. More importantly, they work together to send a continuous message: economic growth is paramount.

The fact that this “statistical chorus” is, for the first time in modern history, being questioned by some of the leading political and economic voices of our time (see next chapter), is one of the most decisive arguments for considering seriously the idea that we might be moving into a period of “life beyond growth.”

The End of Communism and the Victory of Globalized Capitalism

In its brief review of history, this report has focused principally on the institutions and policy mechanisms associated with industrial capitalism and free-market societies. This is because the capitalist system emerged as the acknowledged “winner” in the ideological struggle with state- controlled communism that dominated history in the second half of the Twentieth Century.

In 1992, political commentator Francis Fukuyama published a book-length essay that became, in itself, a symbol of this victory. In The End of History and the Last Man, Fukuyama argued that free-market capitalism was the only effective way to manage a modern state, and that the fall of Communism and triumph of capitalism might mark the end of humanity’s socio-cultural development. Free- market capitalism was, according to Fukuyama, the last and best stage of economic evolution.

Since then, little has happened to suggest that Fukuyama was wrong in that general conclusion. In the wake of the collapse of the Soviet Union, the countries of the former “Eastern bloc” all moved with great speed to adopt the Western capitalistic economic model. This revolutionary shift was accompanied by more evolutionary, state-led decisions in China and India to liberalize markets, open trade, and generally embrace a capitalist economic model.Those few countries that persist (North Korea) or experiment (Bolivia) with state- controlled economic policies are increasingly seen as outliers in a well-established global economic order, structured by myriad trade and currency agreements.

This international trading regime is itself founded on the firm conviction that all growth is good, and that any restrictions on trade that might threaten the overall growth of the global economy — or threaten the opportunity for others to profit from open, globalized markets — are to be avoided. An extreme example of the extent to which this belief is held as predominant preeminent could be seen in mid-2011, when the European Union filed a formal complaint with the World Trade Organization against Canada because the State of Ontario was providing preferential subsidies to Canadian producers of renewable energy, instead of keeping its markets open to all comers. Ethical or environmental arguments might argue for keeping such energy production, and the jobs it can generate, local to Ontario; but global trade rules in the service of global economic growth unrelentingly trump such concerns. Trade rules, together with the rest of the international rules and institutions that now govern the global economy, are among the bricks in the wall that supports the growth paradigm.

Cultural Values Regarding Natural Resources

In recent years, a number of prominent religious leaders have made general appeals to their constituencies to care for the environment. Their calls for stewardship of the Earth and its resources are, however, a very recent phenomenon.