By Giorgio Nebbia

The following piece was published in Capitalism Nature Socialism, Volume 23, Number 2 (June 21012)

The 20th century has been one of hopes and disappointments. The population of the world has increased almost fivefold, which has entailed a tenfold increase in the demand for food, energy, metals, space, housing, and water. There has also been a tenfold increase in the number of people living in urban agglomerations. How long can this last? The early doubts on the continuous growth of the population and of the goods and services may be found in the works of Malthus, who in 1798 published what was known as the “first essay” on population (Anon. 1798), arguing that no matter what technical efforts are made, planet Earth cannot provide the natural resources from which “food” (and by extension water, energy, paper, etc.) can be extracted in sufficient quantities to support the continuous growth of the world population.

This position–though Malthus had no way of knowing it–derives from an ecological knowledge that recognizes the existence of physical and biological limits to the resources of nature. The relentless removal of natural resources–water, minerals, fossil fuels, agricultural products and animals–from physically limited reserves and spaces means that the extent of these resources not only does not grow along with the population, but that these resources decrease as the population grows. In addition, the transformation of natural resources into goods and objects entails the production of residuals and wastes whose emission into natural bodies–water, the soil, and the air–degrades the quality of such bodies and makes them less usable for human purposes. As far back as 1865, the British economist William Stanley Jevons (1906) asked himself how long his country’s coal reserves could last if they continued to be exploited at the rate he observed. The subsequent discovery of extensive petroleum deposits obviated the problem of the exhaustion of coal reserves feared by Jevons, and most British coalmines were gradually closed before they were fully exploited.

In the last century, ecologists and biologists have recognized that each territory of the biosphere has limited resources and a limited capacity to sustain life. In the mid-19th century, Justus von Liebig explained that in a given area of land, the scarcity of even a single nutritional element for a crop was sufficient to cause a decline in harvests. The early decades of the 19th century saw an increase in the knowledge of biological cycles and equilibria. It was realized that the number of individual animals that can live in a pasture or lake depends on the amount of space and food available. As the animal population grows and the availability of space and food consequently decreases, self-limitation mechanisms come into play, and the populations slow their growth until they reach a “limit,” which is the carrying capacity of the territory in question. It is possible that the toxification of the environment by metabolic wastes will lead to population decline.

In the 1930s, in what has been called the Golden Age of ecology, various scientists–the American Alfred Lotka, the Italian Vito Volterra, the Soviet Georgi Gause, the French-Russian A. Kostitzin, and others–elaborated mathematical treatments of the “laws” that describe population growth and decline in confined spaces and with a limited availability of resources and competition among populations living in the same environment. The books of the biologists Umberto D’Ancona (1942) and George Evelyn Hutchinson (1978) offer excellent reviews of the early reconnaissance of the limited carrying capacity of the Earth. In the same decades that human society experienced an unexpected increase in technological innovations and available sources of energy and resources, there was also a corresponding rise in available commodities. Such abundant growth worked to dismiss any pessimistic view of the future.

The cornucopians–the great-grandchildren of Condorcet and Godwin, the authors against whom Malthus wrote his essay–hold that adequate political structures and inventions are able to make available a growing quantity of goods for a growing population, which can look forward to a future of plenty and affluence. Major optimistic writings include those produced in the 1920s in the series Today and Tomorrow, published by Kegan Paul in London and Dutton in New York. In the 1950s, various forecasts of the use of natural and energy resources were published in the volumes Resources for Freedom (Paley Commission 1952) and other books and essays (Putnam 1953; Landsberg, et al. 1963; Barnen and Morse 1963; Kahn and Wiener 1967; Weinberg and Hammond 1971; and Smith 1979).

A deeper insight into the relations between “technical” activities and the surrounding environment began in the 1950s with the protest movements against the explosion of atomic bombs in the atmosphere. The bomb testing released large quantities of long-lasting radioactive isotopes in the earth’s atmosphere and thence into living systems–soil, plants, animals, and humans. Protests also erupted against the use and abuse of synthetic chlorinated pesticides, another source of poisoning of the planetary biosphere, which was denounced by Rachel Carson in her landmark book Silent Spring (1962).

In reaction to these acts of violence against nature, a segment of the public in the industrialized countries, who live in a situation of satisfied needs, demanded an end or limit to actions that could damage the health of present and future generations. Their pressure led to the nuclear test ban treaties, the prohibition of the use of DDT, and various antipollution laws. At the same time, a number of economists and intellectuals (Galbraith 1958; Kapp 1963; Marcuse 1964; Hardin 1968; Ehrlich 1968; Boulding 1970; Commoner 1971; Georgescu-Roegen I 974) recognized the very root of the ecological crisis in the myth of economic “growth” and the endless increase of its only form of measurement, the individual money income, or the national Gross Domestic Product (GOP).

In this climate, a protest movement grew involving students and workers, starting in Berkeley in 1964 and then spreading to Germany, France, and Italy. In Europe it is often belittlingly labelled the “’68 Movement.” The “movement” protested against, among other things, the devastating effects that economic growth in industrialized countries had on the rights of individuals and poor classes and on the natural environment, continuously contaminated and depleted by the destruction of forests, the expansion of cities, traffic, polluting industries, goods and machineries (Nebbia 1994). As far as I know, the first use of the word “dedevelopment,” as an invitation to stop such crises, was by Paul Ehrlich in an article in the journal Chemistry, in February 1970.

The ferment of this climate was clearly understood by the Italian intellectual and entrepreneur Aurelio Peccei, who invited a group of engineers to investigate the possible future of humanity. Peccei commissioned Jay Forrester, an American specialist in systems analysis, and his colleagues, the Meadows, to formulate a forecasting model. They essentially rewrote and numerically solved some of Lotka and Volterra’s differential equations, introducing factors of slowdown and decline in human population growth under the effect of the production of commodities and resulting pollution. In early 1971, their first results began to circulate. A special ecological commission of d1e Italian Senate (Senato della Reppublica 1971) analyzed their work, and a special issue of the journal The Ecologist released an advanced copy of their report in January 1972. The final results were set out in The Limits to Growth, published in May 1972 (Meadows, et al. 1972), to coincide with the United Nations conference on the human environment, held in Stockholm. The book–substantially a manifesto of what has subsequently come to be known as “degrowth”–contains economic and social forecasts projected to an unspecified date in the 21st century. It did not say what will happen, but what could happen in the case of a concatenation of events affecting the whole of the Earth’s population:

- if the population grows, so will demand for food, materials, and goods;

- if the demand for food grows, agricultural production will have to increase;

- if agricultural production increases, the use of fertilisers and pesticides will have to increase also, triggering further depletion and erosion of arable land;

- if the depletion of land increases, agricultural production will decrease and with it the supply of food;

- if the supply of food falls, the number of undernourished or starving people will increase;

- if the demand for materials, energy, and goods increases, industrial production and the extraction of minerals, water, and fuels from natural reserves will increase;

- if the depletion of reserves of natural economic resources increases, there will be an increase in wars and conflicts for the conquest of scarce resources;

- if industrial production increases, environmental pollution and contamination will increase;

- if environmental contamination increases, human health will be impaired.

In short, if the population continues to grow (in 1970 the world population was 3.7 billion and is increasing at the rate of 70 million a year; in 2011 world population reached 7 billion, still rising by 70 million a year), there will be an increase in the conditions–disease, epidemics, hunger, wars and conflicts–that lead to a decrease–perhaps a traumatic one–in the rate of growth of the human population and economies. In order to avoid traumatic situations, a rapid decline in the growth rate of the population (with a consequent slowing in agricultural and industrial production and environmental degradation) should be sought. This would help achieve a stationary society, as suggested much earlier by economists like John Stuart Mill (1865) and Cecil Pigou (1935).

The book published by the Peccei Club of Rome met with contrasting reactions. One was enthusiastic. The book seemed to indicate one way of achieving an ecological and economic balance. Its recipe provided one response to the ferment of student protest, ecological protest, and the claims of workers and underdeveloped countries. It also spoke to the sudden spike in the prices of raw materials and commodities that had begun in the autumn of 1973. Authoritative figures, enchanted by the publicity received by the book, argued that the “limits” could be incorporated into government programs. Sicco Mansholt made them into a manifesto that attracted some public support.

The other reaction was condemnation, with attacks from various fronts. The first and most authoritative was that of vested economic interests, which saw the call for a slowdown in economic growth as a form of subversion that would threaten business, products, industry, and technological development. It mattered little that the call to limit growth came from a group that also included authoritative representatives of the industrial and financial establishment. At that time, they were labelled class traitors who were spellbound and taken in by the tall tales of ecologists–or even communist infiltrators–who preached a halt to the growth of capitalist countries in order to open the gates to the bolshevization of the world.

Another barrage of attacks came from professional economists, who accused the book’s authors of ignorance. They argued that the economy was able to cope, and had always coped, with the problems of scarcity of resources and money–indeed, economics was by definition the science of facing scarcity. Problems had always been and would always be overcome by market providence, which had been invented for the precise purpose of leading us towards the alternative materials and technologies that ensure continuous economic growth, humanity’s only real value and virtue. In an interesting and ironic article, the British scholar Wilfred Beckerman (1972) wrote: “So you can now all go home and sleep peacefully in your beds tonight secure in the knowledge that in the sober and considered opinion of the latest occupant of the second oldest Chair in Political Economy in this country, although life on this Earth is very far from perfect, there is no reason to think that continued economic growth will make it any worse.”

The third source of criticism was the Cacl1olic Church, which had been torn apart by internal divisions on the question of birth control. The Encyclical of Pope Paul VI, Humanae vitae (1968), while recognizing the right to responsible procreation, was opposed to the means of limiting births–whether by abortion, the pill, or other contraceptives. This position was supported by the Catholic economist Colin Clark (1977 [1967]), who argued that the Earth could provide enough water, food, and material goods to support 40 or 45 billion people. The debate on the limits to population growth and the means to achieve this objective deepened the divisions among Catholic women who were sensitive to the burgeoning women’s liberation movements and the new issue of women’s employment. For them, these issues were hard to reconcile with the high number of pregnancies occurring, and also within the Catholic female community in Protestant countries as well as Third World and poor countries. The information in the Limits to Growth i.e., that an “excessive” increase in the population did not solely concern the private lives of couples, but could exhaust the gifts of nature and threaten future generations–presented a serious challenge to the dictates of the Roman Catholic Church.

The fourth front of criticism came from the Left, both the communist parties and the non-parliamentary Left, which in Italy at that time spoke through a number of newspapers and journals– Il manifesto, Aut aut, Bandiera rossa, Potere operaio, Quaderni piacentini, Quaderni rossi, etc. Perhaps the most interesting voice from this part of the political spectrum was that of the Italian writer Dario Paccino whose bestselling book L’imbroglio ecologico (Ecological Fraud 1972) prompted numerous debates and university seminars. Paccino argued that the call for limits to growth was yet another bourgeois trick designed to preserve the privileged position of the ruling class, whose needs were amply satisfied, while keeping the working class in subjection and poverty, both in industrialized countries and in the Third World. The French writer Paul Braillard (1982) also wrote a pamphlet against the Club of Rome and its conclusions.

A rather crude reaction came from the communist countries, where Limits was subjected to fairly close scrutiny. Their basic position was that the disasters foretold in the book were to be expected in capitalist countries, dominated as they were by the perverse laws of individual profit. In a planned socialist society, they argued, the extent of production and population pressure on natural resources and environmental degradation could be regulated by central authorities–that is, by the people–without any danger of disaster or crisis. The Marxists also asserted that the problem of rising populations affected capitalist countries more than the communist world. These strictures were naive. By the end of the 1960s, the socialist countries already had clear signs of environmental disasters caused by reckless economic planning. Besides considerable environmental pollution, the environmental degradation included significant losses in soil fertility as a result of excess production, for example.

All on its own was the critique formulated by the Romanian-American economist Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen (1974) in a number of essays beginning in 1971. To him it was illusory to suggest, as Limits did, to strive for ecological salvation in the achievement of limits to growth. He argued that ecological disaster is inevitable even in a “stationary-state” society with a stable population, production of material goods (however distributed), and use of natural resources. The reason is that entropic depletion is intrinsic not only to the use of energy resources, but to the use of materials extracted from nature. A feasible salvation for humanity was to be found only in “degrowth,”“la décroissance,” which was the title of a collection of essays by Georgescu-Roegen (1979), [1995]), first published in Switzerland in 1979.

The rapid rise in crude oil prices that started in 1973 and went on until 1985, the long Iran-Iraq war, and the local wars over raw materials that punctuated the 1970s and 1980s seemed to corroborate the predictions advanced by the Club of Rome. The same proposal of”halting growth” was reached by a book commissioned by U.S. President Jimmy Carter and published at the end of his term of office in 1980 under the title Global 2000 (Barney 1980). Although the book was rich in data that are still worth reading today, the reaction that greeted it was much more lukewarm than that aroused by Limits because it presented prospects that ran counter to the intentions of Ronald Reagan’s new Republican administration, which was bent on launching a new era of economic growth.

Almost as if to erase any memory of Global 2000, a book by two cornucopians, J.L. Simon and H. Kahn (1984), was distributed on a massive scale through the commercial publishing circuit. Its deliberate aim was to demolish the forecasts of Global 2000 and explain that the earth’s resources were available in abundance and in no way hindered the new political project of expanded trade to spur economic growth that is now remembered as “the 1980s.” One essay by Cesare Marchetti (1979) examined the possibility of an Earth inhabited by 1,000 billion people!

To appease the economic establishment, in 1987 the United Nations Commission on Environment and Development published Our Common Future, also known as the Brundtland report (UN World Commission on Environment and Development 1987). This reassuring report suggested that it is possible to build a society through “sustainable development” in order “to meet the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” The idea of sustainability has since become both a popular myth and a term devoid of meaning. Although the adjective “sustainable” is attached to numerous political activities, products and services, this improbable idea, which a popular proverb summarizes as “you can’t have your cake and eat it, too,” is too rarely questioned.

When the first proposals of “degrowth” were presented, the geopolitics of the world and of narural resources was very different from what they are now. In the 1970s the world was conventionally divided into three parts along the lines suggested by the French demographer Alfred Sauvy. The First World was made up of industrialized capitalist countries, basically the American empire and its satellites. The Second World included the communist or socialist countries, basically the Soviet Union and its European satellites, which were industrialized to varying degrees. The Third World comprised a large number of other countries, some gravitating around the First or the Second World, some non-aligned, some industrialized, others in the process of industrializing, others poor, and still others extremely poor.

A brisk interchange of raw materials, goods and technology took place among these three groups. Some exported raw materials taken from their stock of natural resources (forestry products, livestock, minerals, energy sources). Others exported or sold labor, and still others exported technology, machinery, or manufactured goods.

The capitalist countries thought that the satisfaction of their citizens’ needs could be assured by private property and its obedience to the “marker,” an entity based on the concept that from work and raw materials each individual must gain the maximum amount of money that will enable her/him to purchase the maximum possible amount of goods and services. By their own intrinsic laws, capitalist societies can survive only through a continuous growth in the production and consumption of goods. This, of course, occurs at the cost of a growing extraction and contamination of the planet’s natural resources.

The socialist countries thought that the human needs of their citizens could be satisfied by the state, which not only owned the material assets of the land and the means of production, but also planned how to use and distribute those assets and how to employ human labor. A society with a planned economy would, in principle, be able to extract and use its natural resources frugally to best ensure the satisfaction of its citizens’ needs, with goods and services planned by the government while slowing the depletion of its natural resources. However, what actually happened was that the Soviet Union engaged in a race to reach and overtake the United States in the production of goods. Widespread ecological ignorance or underestimation of the environmental impacts of this course led to environmental devastation and poverty for both the society as a whole and the individuals living in it.

For their part, the countries of the Third World correctly recognized that they could achieve freedom from poverty with growth in production and the supply of goods and services. Mass media–especially television–in developing countries artfully propagandized their populations with the capitalist creed, which preaches that the greatest happiness is to be found in the possession of goods similar to those television portrays as filling the homes of the industrialized West.

In the 1980s, the deification of the market, private property, and the conquest of goods also contributed to the gradual destruction not of realized communism (what fell apart was a perverted version of socialism, not true communism), but of any ideal of a different relationship between human beings, objects, and natural resources. The result was unbridled competition between individuals, social groups, companies, and states on a terrain that was never ideal but only commercial. This resulted in the acceptance of any form of violence as a means to increase money, and therefore goods, in one’s possession, along with the use of the Gross National Product (GNP) and its continuous increase as the only index of well-being, happiness, and the prestige of both one country over another and of one individual over another. Because “globalization” has come to mean the realization of the grand commercial ideal of capital, the spread of needs, and the ideal of consumption, the exploitation of nature and labor is now accelerated in all countries. To obtain the growing quantities of goods, poor people have to exploit their own bodies, sell their labor at an increasingly low cost, as well as sell the space they occupy, the water that feeds their land, the forests, etc. In the capitalist system, because the increase of monetary wealth in circulation works to impoverish the majority of the Earth’s individuals (Pope John Paul II at various times denounced the growing inequality between the rich and poor in global society as a scandal), it accelerates the depletion and growing contamination of nature. In this social and economic context, characterized by the economic crisis of recent decades, the philosophy of “degrowth” has obtained some acceptance, especially in the middle classes of industrialized countries. But the main question remains unresolved: degrowth of what and whose?

The welfare and survival of people depends on the availability of food and water, energy sources, machines, domestic appliances, buildings, means of transport and communication, education and sanitation. Apparently intangible needs also require material goods: health, dignity, and freedom are not possible living from hand to mouth, with no home or food, surrounded by dirty water. Knowledge is more difficult without paper and the material means of long-distance communication, be they the skins on the drums of the jungle telegraph or the silicon in computers. Material goods can be obtained only through the human activity of extracting minerals, stones, fuels, vegetable matter, animals, water, air–all assets provided by nature–from the biosphere and transforming them into the goods, objects, and machines that go to make up the technosphere: the universe of manufactured objects. After varying lengths of time, the objects used in the technosphere are inevitably transformed into waste and refuse which return, in one form or another, to the biosphere, decreasing the availability of natural resources because of pollution and depletion.

Humanity survives by maintaining a continuous circulation of matter and energy from the biosphere to the technosphere and back to the biosphere (nature-commodities-nature). Commodities are produced not by means of money or commodities, but by means of nature. Since the resources of the biosphere are limited–even though they seem enormous–because of the ineluctable principle of rhe “entropic” depletion of energy and matter (“matter matters too,” Georgescu-Roegen [1974] explained) passing through the technosphere, depletion and deterioration of the “natural” quality of the reserves remaining for present and future generations are part of the functioning of the technosphere. Technology may reduce the mass of materials required per unit of service provided, but the advent of an intangible or dematerialized society is a myth. Irrespective of the rate of population growth and increased demand for material goods–whatever the cornucopians might say–a steady-state society is neither conceivable nor achievable. The same applies to a “sustainable” society and development. The current rates of extraction of material resources and contamination of the remainder are unsustainable. All we can do is to envisage a system of human and international relations that are less unsustainable.

Let’s begin with population, whose degrowth cannot be reasonably foreseen before the second half of the 21st century. In 2011, global population reached 7 billion, increasing at the rate of about 70 million per year. The population of the industrialized countries totals 1.5 billion inhabitants, and these populations are aging, with a strong increase in the elderly (65 and older). Many industrialized countries are also seeing an increase in immigrants, especially from poor countries. There is some slowing of the rate of increase in the rapidly industrializing countries, which collectively have about 3 billion people. The main increase in population is taking place in the poor and very poor countries, which togerher have approximately 2.5 billion people.

Let’s assume the world population is divided into three classes: the “emerged countries,” “emerging countries,” and “submerged countries.” Emerged countries are those that have achieved a relative high level of consumption and satisfaction of the needs of the majority of its citizens. Emerging countries are those involved in a rapid industrialization and increase of consumption, at least for a fraction of the population. Submerged countries are those where conditions for most of its citizens are below a reasonable (whatever this word may mean) standard of living, availability of food, shelter, energy, education, sanitation, and work. Human rights, which can only be achieved through freedom from misery, are largely absent for inhabitants of submerged nations.

Let’s assume a distribution of the world population among these three classes and that their needs, both physical goods and services, may be expressed in an arbitrary unit characterized as the amount of “energy” available to the persons of the countries of each “class.” Let’s also assume that the availability of global “energy” corresponds to about 500 EJ/year (1 EJ = 1,000,000 GJ), similar to current consumption levels (Table I ).

Now let’s imagine a situation sometime between 2020 and 2025 in which the world population has grown according to present trends and that the “goods” to satisfy total needs remain steady, according to the “official” definition of “sustainable development” (Table 2). The situation is far from any “degrowth” project or any demand for equity. In this scenario, the per capita availability of “goods” for poor countries increases slightly. The availability of goods for emerging countries also increases slightly, while the availability of goods for the steady-state population of emerged countries “decreases” from 180 to 110 GJ/person per year. Such “degrowth” of the rich would result in only a small decrease in the misery of the poor. It would also mean a 30 to 40 percent decrease (compared to current values) in the number of cars and amount of electricity, housing, winter heating, summer refrigeration, food, furniture, clothing, and so on in industrialized countries.

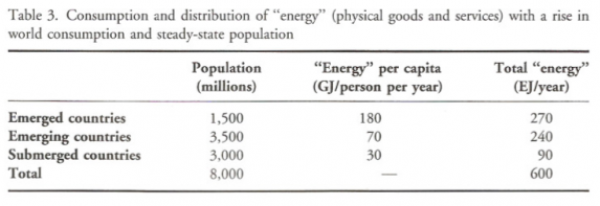

A less drastic situation (Table 3), assuming an increase of total “energy” consumption from 500 to 600 EJ/year, would at most achieve a small reduction in poverty for the poor, while leaving current levels of per capita energy consumption in industrialized countries unchanged. This would mean further increases in the extraction of natural resources from natural bodies with corresponding rises in emissions of gases and other wastes in natural sinks. Furthermore, it would only marginally alleviate the misery for the expanding masses in the non-industrialized countries.

These thought experiments suggest that a “degrowth” project may be well and good for individual changes of attitudes and consumption by part of a small happy fraction of relatively wealthy people in industrialized countries. However, even the decrease from 180 to 110 GJ/person per year in the emerged countries does not seem to be enough of a decline in pressure on the planet as whole. Because of the amount of ecological damage already done, any relief in pressure on natural resources will require severe changes in the economic rules of the present society, which in turn will mean limits and curtailment of individual freedom and avidity. Major changes in the consumption patterns of the rich are required to alleviate just a little the misery of the poor. If for no other reason, apart from caring about the destiny of the planet and its ecological equilibrium, the powerful have a self-serving motive: to decrease the rebellion and violence of the poor that may lead to a scenario of fear and instability for the rich.

References

Anon., [T.R. Malthus]. 1798. An essay on the principle of population, as it affects the future improvement of society, with remarks on the speculatiom of Mr. Godwin, M. Condorcet and other writers. London. June 7.

Barnen, H. and C. Morse, eds. 1963. Scarcity and growth: The economics of natural resource availibility. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press.

Ramey, G.O., ed., 1980. The Global 2000 Report to the President, 3 volumes. Washington, D.C: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Beckerman, W. 1972. Economists, scientists and environmental catastrophe. Oxford Economic Papers 24 (3): 327-334.

Boulding, K.E. 1966. The economics of the coming Spaceship Earth. In Environmental quality in a growing economy. H. Jarrett, ed. 3-14. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press.

______. 1970. Fun and games with the Gross National Product: The role of misleading indicators in social policy. In The environmental crisis: Man’s struggle to live with himself. H.W. Helfrich, Jr., ed. 157-170. New Haven: Yale Univ. Press.

Braillard, P. 1982. L’imposture du Club de Rome. Paris: PUF.

Carson, R. 1962. Silent spring. Boston: Houghton-Miffiin.

Clark, C. 1967. 1977. Population growth and land use. London: Macmillan.

Commoner, B. 1971. The closing circle: Nature, man, technology. New York: Knopf; New edition, in Italian. 1984. II cerchio da chiudere. Milano: Garzanti.

D’Ancona, U. 1942. La lotta per l’esistenza. Torino: Einaudi. Ehrlich, P. 1968. The population bomb. New York: Ballantine.

_____. 1970. Dedevelopment. Chemistry 43 (2).

Galbraith, J.K. 1958. The affluent society. Boston: Houghton-Mifflin.

Georgescu-Roegen, N. 1974. Energy and economic myths: Institutional and analytical economic essays. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

______. 1979, 1995. Demain la decroissance: entropie, ecologie, economie, I. Rcns and J. Grinevald, eds., Lausanne: Editions Pierre-Marcel Favre and Lusanne: Sang de la Terre.

Hardin, G. 1968. The tragedy of the commons. Science 162: 1 243-1 248.

Hutchinson, G.E. 1978. An introduction to population ecology. New Haven: Yale Univ. Press.

Jevons. W.S. 1906 [1865, 1866]. The coal question London: Macmillan.

Kahn, H. and A.J. Wiener. 1967. The year 2000. Croton-on-Hudson: Hudson Institute.

Kapp. K.W. 1963. The social costs of business enterprise. Bombay-London: Asia Publishing House.

Landsberg, H.H., L.L. Fischman, and J.L. Fisher. 1963. Resources in America’s future. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press.

Marchetti, C. 1979. 1012: A check on the Earth-carrying capacity for man. Energy 4: 1107-1117.

Marcuse, H. 1964. One-dimensional man. Boston: Beacon Press.

Meadows, D.H., D.L. Meadows, J. Randers, and W.W. Behrens. 1972. The limits to growth: A report for the Club of Rome’s projet for the predicament of mankind. New York: Universe Books.

Mill, J.S. 1848 [1865]. The stationary state (Book IV, Chapter 6). In Principlts of political economy, with some of their applications to socinl philosophy.

Nebbia, G. 1994. Breve storia della contestazione ecologica. Quaderni di Storia Ecologica (Milano) 2 (4): 19-70.

_____. 2005. Risorse naturali e merci. Una critica ecologica del capitalismo. Milano: Jacabook.

Paccino, D. 1972. L’imbroglio ecologico. L’ideologia della natura. Torino: Einaudi.

Paley Commission. 1952. The President’s Materials Policy Commission: Resources for freedom. Washington, D.C: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Pigou, A.C. 1935. The economics of the stationary state. London: Macmillan.

Putnam, P.C. I953. Energy in the future. New York: Van Nostrand.

Senato della Repubblica. 1971. Problemi dell’ecologia, 3 volumes. Roma: 1971.

Simon, J.L. I 990. Population matters: People, resources, environment, and immigration. New Brunswick and London: Transaction.

Smith, V.K., cd. 1979. Scarcity and growth reconsidered. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press.

The Ecologist. 1972. A blueprint for survival. The Ecologist 2 (1): 1-43.

UN World Commission on Environment Development 1987. Our common future. London: Oxford Univ. Press.

Weinberg, A. and R.P. Hammond. 1971. Global effects of increased use of energy. Paper presented at the Fourth International Conference on the peaceful uses of atomic energy. September 6-16 in Geneva, United Nations.